Red Lipstick’s Evolution Across the MENA Region

Tracing red lipstick’s journey through ritual, rebellion, and reinvention across the MENA region.

Red has been beauty’s most enduring shade.

From the make-up pots of ancient Sumer to 50’s movie sets to (most likely) your bedroom, it’s the thread that stitches together centuries of faces and rituals.

But the real story isn’t just what it’s made from, but what it gets made to mean. Think of Eve and the apple – desire recast as “forbidden fruit.” Red lipstick feels like the sequel to that myth: not the temptation itself, but the evidence. A mark that says pleasure happened here, and it can’t be taken back. That’s the strange power of a single colour. It can mean vitality and transgression at once. Because red is never just red. It bleeds into politics, into desire, into the daily choreography of being seen.

What follows is an archaeology of that colour: a timeline of red lipstick across the Middle East and North Africa, moving through ritual, rebellion, and reinvention.

What follows is an archaeology of that colour: a timeline of red lipstick across the Middle East and North Africa, moving through ritual, rebellion, and reinvention.

Ancient Sumer (5300 B.C.E. – 1940 B.C.E)

Our story begins in Ancient Ur, around 3500 B.C.E., with Queen Puabi. She ruled one of Sumer’s great city-states, among the world’s first known urban civilizations, located in modern-day Iran. Legend has it that during one of her public appearances, she was seen with lips tinted red. Soon, the shade spread through the city, worn by women and men alike, an early echo of beauty as imitation, influence, and power.

Archaeological research suggests the pigment was made from white lead and crushed red stones – beauty’s first flirtation with danger. Perhaps Eve’s apple was never just a metaphor, but an early lesson: that temptation, poison in disguise, has always tinted the lips.

Rather than marking gender, the way rouge was stored revealed class. The wealthy stored their pigments in beautifully encrusted metal saucers and bowls, while others used simple clay or shells. Not unlike today, when the gulf between a drugstore lipstick and a Louis Vuitton Rouge lies less in colour than the container that holds it. Excavations led by Sir Leonard Woolley in Ur’s Royal Cemetery revealed that those who could afford it were buried with their lip paints carefully stored besides thems. This ritual shows that even in the afterlife, beauty – embalmed as lipstick – still had a place in eternity. Ancient Egypt (3100 B.C.E. – 30 B.C.E.)

Ancient Egypt (3100 B.C.E. – 30 B.C.E.)

As the story of beauty travelled down the Nile, lipstick culture continued to be inseparable from the divine. In ancient Egypt, divinity was synonymous with perfection, and make-up became the medium through which both could be pursued. The dark brows, kohl-lined eyes, and red-tinted lips that defined the ‘perfect’ face still echo through our contemporary ideals of beauty. Gather the fragments of that world, and the pursuit of beauty reveals itself everywhere – in painted walls, carved hymns, and the faces of their gods.

On one Middle Kingdom monument (Fig. 2), a woman named Ipwet gazes into a mirror, dabbing rouge onto her cheeks. Centuries later, in a Nineteenth Dynasty papyrus (Fig, 3) often called the “erotic papyrus,” a courtesan appears with a lotus flower tucked into her wig, painting her lips as she studies her own reflection in a metal mirror.-207ebb8b-d375-4755-945a-441705525479.jpg)

-086bc300-d851-48a8-8d45-f5378e5b1095.jpg) The most important material used in red pigment was red ochre, a naturally occurring iron oxide sourced from from Aswan and the Oases. The pigment was made from coloured clay that was mined, washed, then dried under the desert sun. Beyond beauty, ancient Egyptian medical texts also prescribed this red ochre for healing eye infections, burns, wounds, and animal bites.

The most important material used in red pigment was red ochre, a naturally occurring iron oxide sourced from from Aswan and the Oases. The pigment was made from coloured clay that was mined, washed, then dried under the desert sun. Beyond beauty, ancient Egyptian medical texts also prescribed this red ochre for healing eye infections, burns, wounds, and animal bites.

If beauty in ancient Egypt was divine, it was also democratic. Both men and women painted their faces – not simply vanity, but also vitality. Make-up, in this sense, was political long before it was aesthetic. The freedom with which women painted their faces in history is often closely linked with the freedoms and rights they held in life – and in Egypt, those freedoms were unusually expansive. Women could own and inherit land, run businesses, and bring cases before the courts.

Yet the same tools that symbolized autonomy have often been recast through myth. Power, when embodied by women, many times is rewritten as seduction. Figures like Cleopatra VII sit at that intersection, her beauty remembered as both power and peril. Her supposed use of crushed beetles for pigment in her red lipstick is likely legend, but a potent one: the base red ochre mixed with animal fat, was then darkened with carmine or iodine (literal poison) to achieve the perfect shade of red. These highly toxic concoctions, and the retellings of powerful women, blur the line between allure and danger. Classical Era and Early Islamic Era (8th - 13th Century)

Classical Era and Early Islamic Era (8th - 13th Century)

As Egypt moved from the Roman and Byzantine periods, the story of beauty began to shift. During these Classical eras (332 B.C.E. – 641 CE), the ancient pigments endured, but their meanings changed. Red, once divine and protective, became increasingly entangled with desire and danger. Under Greek and Roman influence, beauty was recast through ideals of modesty and morality, and by the time Christianity took hold, the same painted lips that once signified vitality came to suggest vanity and moral temptation.

Through the Islamic Golden Age, cosmetic recipes continued to circulate in Coptic and Arabic manuscripts, bridging medicine and adornment. Texts described rouges made from vegetal dyes like carthamin and tarthuth, and physicians prescribed pigments for both healing and beauty. But alongside this legacy of artistry and science came debate: some scholars questioned whether red pigment, especially on the lips, veered into vanity – an early echo of the moral policing that still shadows contemporary women’s self-expression.

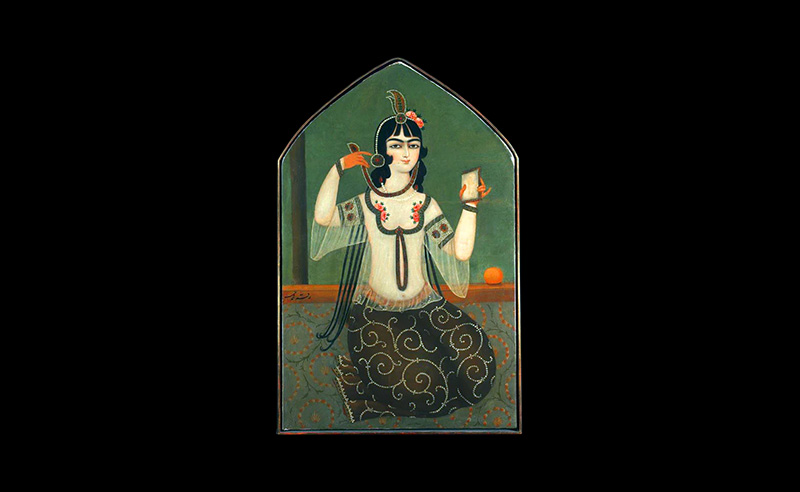

Colonial Modernity (19th-20th Century)

Colonial Modernity (19th-20th Century)

Centuries later, as colonial modernity swept through Egypt, red lipstick was reframed as a marker of Westernization. In the West, it had been recast as a symbol of female empowerment – worn defiantly by flappers in the 1920s, by suffragettes marching for the vote, and by women in “We Can Do It” posters who painted their strength as vividly as their lips. Sold in magazines and posters, these fashions were then remarketed as the signature of the “modern Arab woman” – becoming shorthand for emancipation, progress, and cosmopolitan identity. Ironically, the same hue that colonial-era beauty ads claimed to introduce to the region had roots in the very civilizations they sought to overwrite.

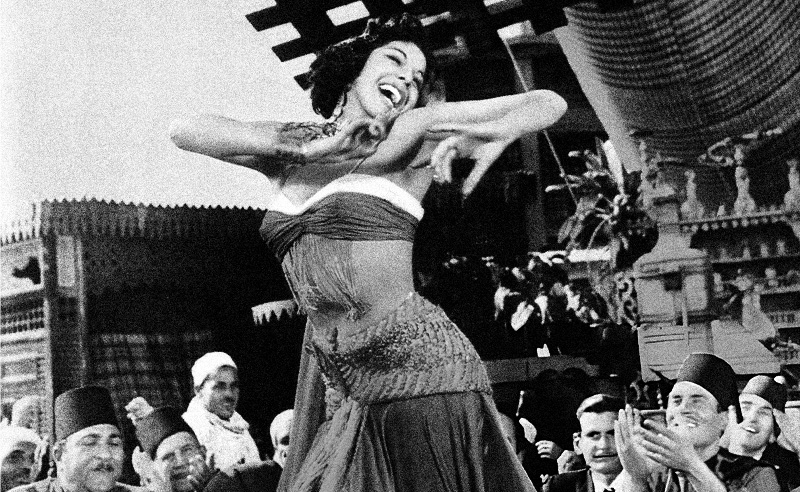

Local women and filmmakers didn’t merely accept this imported script, they transformed it. Post WWII, during the Golden Age of Egyptian cinema, the screen became a battleground for how femininity was seen and defined. Hind Rostom, with her unapologetic sensuality, embodied a kind of rebellion that refused to be contained. Faten Hamama, by contrast, brought quiet strength to her roles. And Samia Gamal, the dancer-turned-actress, used movement itself as liberation, her smile painted red like a signature of self-possession.

Through them, the red lip ceased to be a Western accessory and became something far more radical: an emblem of Arab womanhood on its own terms. It was no longer a borrowed image. The red of lipstick became a marker not of capitulation but of persistence, echoing the same defiance once crushed into the pigment in Ancient Egypt.

Through them, the red lip ceased to be a Western accessory and became something far more radical: an emblem of Arab womanhood on its own terms. It was no longer a borrowed image. The red of lipstick became a marker not of capitulation but of persistence, echoing the same defiance once crushed into the pigment in Ancient Egypt.

Contemporary Day

Perhaps the story of red lipstick has always been a story about an appetite for freedom, about what lingers after the bite. The ‘forbidden fruit’ was never really about temptation; it was about proof of indulgence. Evidence that something was desired… and tasted.

When we reach for red today, in the bathroom mirror or a car window’s reflection, we’re part of that lineage, of women and men who painted their lips not just to be beautiful, but to exist more vividly. The stain has travelled through temples and cinemas, through the hands of alchemists and actresses, through centuries of worship, shame, and survival. And when you meet your own reflection, perhaps you’ll see it there too.

Bibliography:

Schaffer, S. (2006) Reading Our Lips: The History of Lipstick Regulation in Western Seats of Power. Third Year Paper, Harvard Law School.

Lugatism (2022) ‘Medieval Arab women’s makeup’, Lugatism, 25 September. Available at: https://lugatism.com/2022/09/25/medieval-arab-womens-makeup/#4_Rouge_and_blush

Eldridge, L. (2015) Face Paint: The Story of Makeup. New York: Abrams.

El-Kilany, E. and Raoof, E. (2017) ‘Facial Cosmetics in Ancient Egypt’, Egyptian Journal of Tourism Studies, 16(1), pp. 1–19.

Waldo, K. (n.d.) Makeup Through Time: Social Status, Expression, & Gender Roles. [Unpublished manuscript/website – specify if journal, book, web page etc.]

El Shokry, (n.d.) ‘Ancient Egyptian Cosmetics’, Dr. Shokry El, Volume 17, Issue 24.

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Jan 29, 2026