Within the Folds of Zine-Making in Egypt

With traditional publishing gradually inching more and more out of reach, people on the Egyptian arts and culture scene take to single sheets of paper to communicate.

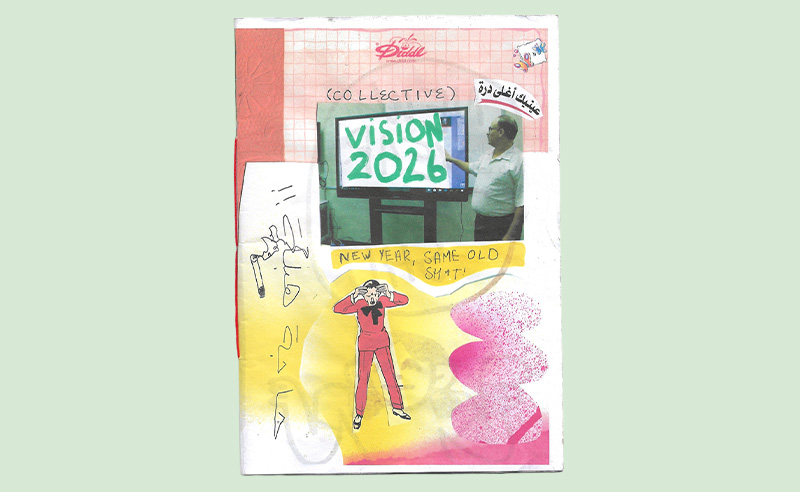

At a kitchen table in Alexandria, six strangers and I put together a small book one page at a time, mostly sporadically - a list of someone’s New Year’s resolutions, an illustration of someone standing at the top of a mountain, a hypothetical wedding born out of a found magazine headline, a comical vision board. The book’s cover was made in seven minutes, powered by tea and a cake that didn’t rise. What resulted was a zine, made in a six-hour workshop for zine-making by Alexandria-based artist Tiana Kader.

In the same month, at least three other workshops took place across the country. For creatives in Egypt, both amateur and professional, the practice of zine-making has gradually become more of usual programming.

The prestige of both the publishing and fine art industries stands on the foundation that not just anyone can be published. There is a clear inaccessibility, a difficulty to penetrate, which has led countless publishers and galleries to function independently, with the goal of spotlighting the underdog. Within the gaps of that network flourishes an even more independent model of publishing, two degrees removed from traditional publishing - one that lives in folds of paper, fun scribbles and cheap photocopying - through zines.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines zines as ‘noncommercial often homemade or online publication usually devoted to specialised and often unconventional subject matter’. In the real world, Egyptian zine-makers emphasise various characteristics as the defining point of what makes a zine: price, speed, spontaneity, independence, how personal they are or simply the fact that they’re made on a single folded sheet of paper. The breadth of definitions is an endless point of discussion between zine-makers, but it is always discussed casually, with the shared understanding that, at the end of the day, this is a medium created for freedom, so its definition can only be loose.

The reason zines exist on the fringes of both the publishing and fine art industries is that they’re either too personally specific, or because it’s simply something too risky to be published formally. No one wants to publish the personal feelings of a regular person, but to have them put in print, out of the control of Silicon Valley billionaires, is invaluable. Zines essentially exist within that DIY liberative space. The medium became popularised, and took on its distinct scrappy visual identity, during the 1990s Riot Grrrl movement in the US, when feminist groups and individuals started printing out leaflets to spread information newspapers would not publish. Gradually, that grew into a method of sharing niche interests, and trading those interests through zines. I was introduced to zines through a documentary about the movement and they, at first, charmed me, but I thought of them as inherently foreign.

The medium became popularised, and took on its distinct scrappy visual identity, during the 1990s Riot Grrrl movement in the US, when feminist groups and individuals started printing out leaflets to spread information newspapers would not publish. Gradually, that grew into a method of sharing niche interests, and trading those interests through zines. I was introduced to zines through a documentary about the movement and they, at first, charmed me, but I thought of them as inherently foreign.

Zines remain a foreign concept despite their abundance in Egypt. “The first time I got approached about a zine, I didn’t understand what was being said,” archivist, writer and artist Alaa Abdelhamid tells me, “It’s not something that’s in our vocabulary. But a closer look at the history of print in Egypt shows that publications that would be identified as zines did exist in our history. A group of writers in the Delta used cheap photocopying to distribute their poetry. Another group used the brochure for an exhibition to explore various topics that concerned them both visually and in writing.”

Abdelhamid and I struggled to translate the term ‘zine’. No Arabic word could fit it perfectly, because it is an inherently Western - American - concept. According to Abdelhamid, the term ‘Master’ - as in master copy “الماستر” - is as close as possible to ‘zine’. The term ‘matweya/مطوية’ - translating to ‘folded’ - also comes close. Most zine-making artists simply refer to them as zines - ‘زِين’. Esraa Kamal, an artist who gives workshops on zine-making, publishes her work on a platform titled simply ‘Zine Bel 3raby’.

When they originated, zines were popular as a response to the rapid centralisation of corporate media. They were created by people on the margins of the Left - those who are not respectable academics - in order to create a vessel where the non-published minority could communicate their thoughts as well. In his book, Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture, zine researcher Stephen Duncombe describes the craft as a breath of fresh air in Leftist discussions, “Where years of sterile academic and political debates on the Left often placed culture in the past, dismissed as irrelevant to the 'real struggle,' zines seemed to form a true culture of resistance.”

To Dennis Farnsworth, the founder of Shoebox Magazine, the independent publishing of his publication replicates this sentiment. He tells CairoScene, “In a lot of bookstores I go to, I feel like there are all these beautiful books that are super inspiring, but how would I ever be able to participate in them?” asks Farnsworth, “How would I ever be able to be in one of these magazines, or to engage with them on a personal level? It's completely beyond my scope, and they would never even think about me. Shoebox, to me, is a way to try to challenge this elitism in arts and culture spaces.”

While Shoebox isn’t exactly a traditional zine, its structure is akin to what would be a sort of communal zine. It’s a non-periodical magazine that takes submissions from anyone, often with little connection to a theme, and in various mediums: articles, personal essays, Q&As, poetry, painting, sketches, collage, sculpture, and even performance pieces. The production process is DIY: Farnsworth saves money from his grant, buys paper from Attaba, and spends five hours waiting for it to be printed at his university press.

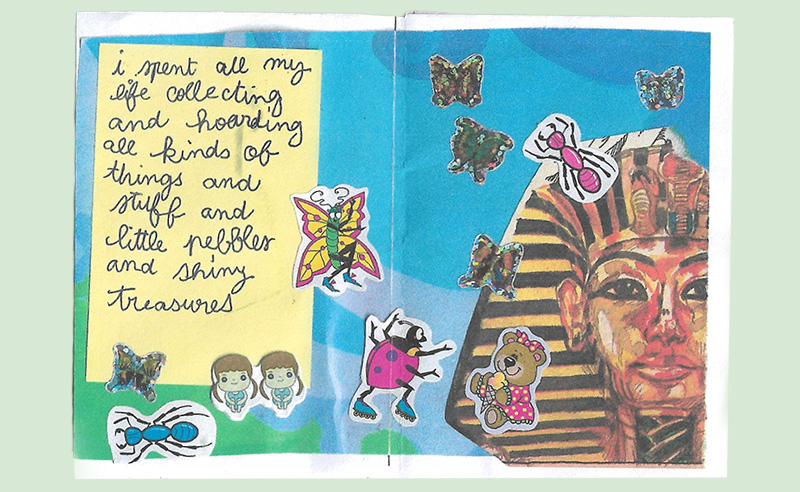

The process for zine-making, by definition, typically follows the same model; it’s experimental, oftentimes messy and held together by a thread (sometimes literally). Esraa Kamal, an artist and regular instructor of zine workshops in Cairo, tells me that she usually carries a folded up piece of paper in her pocket, ready to fill it out and create a zine. “My drawer is full of zines that I never really published; I sort of use them the way I use a sketchbook.” Kamal’s first zine was created in a moment where she desperately, burningly, needed an outlet to express herself. Then they became more casual; about a day, a book she read, a passing thought. Production, design, and publishing came secondary.

Kamal started hosting zine workshops for children Throughout our conversation, she refers to the practice as “play”. She invited me for a playdate at her studio. “I started out hosting these workshops for children, because children are less inclined to strive for perfection than adults. They’re better able to create just for the sake of creation.” Kamal also taught children to study using zine-making.

The air of nonchalance with which Kamal approaches zine-making is shared by many artists in the trade. Multidisciplinary artist Norhan Hawala, who experimented with everything from sculpting to prose to art management, tells me she gravitated towards zines because they’re just easy to make; they’re quick, versatile and simple. “The first zine I ever made was for my niece,” Hawala says, “I wanted a quick way to teach her about mental health and well-being in a simplified way, and it was just what I gravitated towards doing.” Since then, Hawala has made more and more zines, eventually displaying them for sale, which she prefers to do in a fair.

When I spoke to Hawala, it was the morning after her participation in Underground Social’s art market, at which she displayed her zines alongside a collection of personal paraphernalia: books, trinkets, etc. Hawala tells me she does this because, to her, this art is deeply personal; it has to exist around a conversation, around a display of who she is.

To many, this deep personal connection is core to the making of zines. But a more commercial model also exists; at Rizo Masr, a risograph print studio in Maadi, zines are used simply as a medium for communication. Youssef Sabry, the founder, wanted to utilise them after seeing how they were used in London, and his team of illustrators come up with concepts, research them, and publish them as pocket-sized booklets of information. There’s zines about houseplants, commuting in Cairo, how to navigate a one-day trip to Alexandria and much more.

To Amira El-Sheikh, the head designer at Rizo, the practice of zine-making is one where professional artists can both let loose and challenge themselves. When she researches a topic for a zine, it naturally brings up a lot of information, which she then has to distill into a visual design that can fit on a single sheet of paper. Within this model, El-Sheikh doesn’t think of zines as easy or casual, but as a visual challenge she’s excited to take on.

On the same shelf at Rizo, the contemplative black and white photography of Malak Kabbani, a London-based Egyptian photographer, sits beside a colourful zine about the history of torshi. Above them is a zine about cats, below them one about how someone feels about the night told in simple illustrations and poetry. Kabbani approaches the medium as an economically reasonable, relatable way to put together photography collections. She works with photographers from across the world, putting together themed collections that are then printed in risograph.

“These zines are like a medley of moments from my life,” Kabbani tells me, “The casualness of them distances them from an air of preciousness, it makes them more intimate.” Esraa Kamal echoes a similar sentiment, “Zines don’t partake in the perceived ‘sanctity of art’. I can tear them up, lose them, throw them away, which means I get to do whatever I want on this single sheet of paper.”

The spectrum of zines is essentially limitless, in both topic and production value. The initial purpose of zines, back in 1990s America, was accessibility. They were free or cost a dollar, and even then they were tradable. Today in Egypt, accessibility is no longer the only purpose. Zines are also used as an extension of an artist’s practice; a zine that comes in a tin box with a selection of topical paraphernalia will cost more that a cheaply printed single sheet of paper.

“The fact that zines, as a medium, are able to accommodate both the serious and the frugal - the fact that you can both make a zine purely for aesthetic purposes or for activism - is what’s beautiful about them,” says artist, curator and zine-maker Marwa Adel Benhalim.

After they are made, in someone’s bedroom, in a research workshop, or after weeks in a studio, where do zines go? The medium exists at the border of artistic practice, and on the sidelines of the publishing industry, which means they’re hardly found in art galleries or traditional bookstores. As a result, every year, zine-makers find themselves displaying their work almost exclusively at the annual Cairo Art Book Fair.

“The fair gives us a deadline,” Farah Hallaba, the co-founder of photography-focused artist collective Safena 7 and research platform Anthropology Bel 3araby, “We have to print our work by November so we can have a table full of books by December. It also gives our work a social life, a chance to see and be seen, and then to be discussed.”

The Cairo Art Book Fair connects artists and publishers from across the world. “When we founded Cairo Art Book Fair, zines weren’t specifically on our mind,” says Nour El Safoury, the fair’s co-founder and founder of alternative bookshop and publishing house Esmat, “We were interested in all kinds of publishing that doesn't have a place in the dominant book market - zines, art books, experimental prints - everything on the periphery of the commercial publishing sphere.”

Beyond publishing, the Cairo Art Book Fair founders similarly view the event as an opportunity to create visibility for independent publishers. Marwa Adel Benhalim, who is also the fair’s co-founder, tells me, “Every year, this fair gives us an opportunity to celebrate the makers of these books, and to create a rooted discussion around how independent publishing functions in the region.”

Despite not being in the initial plan for the fair, El Safoury tells me that zines are now very integrated in the vision for Cairo Art Book Fair because of their intrinsic independence. “Zines allow for new, fresh voices to be part of the publishing scene. The fair allows for that widespread distribution, that meeting of work, but in its being an event, it’s not long term. What the fair done is facilitate a moment of connection, after which displayed zines can find circulation in art spaces and workshops.”

Illustrator Yara Gharib made a collection of zines titled ‘Lony Masry’ for her graduation project, with the intention of displaying them for sale in kiosks around Cairo for the price of a pack of gum. “The series discusses whitewashing in various contexts, so I thought of it as something everyone should have access to,” Gharib tells me. Due to logistical difficulties, Gharib was not able to sell her zines in kiosks, but the idea is still there.

El Safoury understands what the fair represents to participating artists, but she also recognises that it is very fleeting. Instead, she poses a more permanent, supportive infrastructure for publishing, one that is both informal and open. Through her work in Esmat, El Safoury presents a year-round effort to support independent publishing. “To sustain the practice of zine-making in Egypt, we need formal and informal networks for circulation: book shops, events, in a gallery or someone’s house. The presence of specialised bookshops that each tackle a model of publishing makes everything more open & more diverse for all of us.”

- Previous Article ‘Sekket Rizq’ Connects Care Graduates to Delivery Jobs

Trending This Week

-

Feb 16, 2026