The Man Who Doesn’t Want to Reinvent Downtown Cairo

Mostafa Salem dreams of restoring Downtown Cairo’s historic fabric without turning it into a closed museum.

Talaat Harb’s cracked sidewalks, faded shopfronts, and sagging balconies tell a story Cairo has grown used to ignoring. But for Mostafa Salem, moving slowly through the chaos, each chipped cornice and broken tile is a call to attention.

In a city where past and present grind together like faulty gears, Salem’s work - stubborn and quiet - feels almost radical. Through his firm, Coconut Interiors, he is part of a small but determined movement trying to revive the beating heart of Cairo’s historic Downtown, Wust El Balad as a set piece, as a nostalgic fantasy, as a living memory.

It’s a mission that demands a different kind of heroism: one that resists erasure not with grand announcements, but with patience, pragmatism, and an unglamorous fidelity to detail.

Salem knows that restoration can't remain an elite conversation among architects and developers. So, armed with nothing more than a smartphone and a sharp eye, he has turned to TikTok and Instagram, platforms more often associated with dance trends and makeup tutorials than architectural activism.

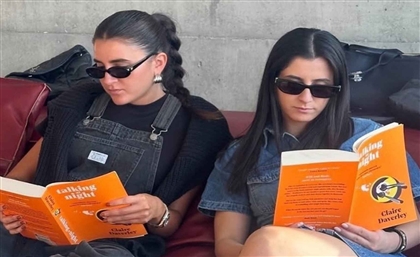

In short, snappy videos filmed from the sidewalks of Wust El Balad, he films the Evergreen Tower, dusty cinemas, old colonial staircases, overlaying them with imagined "after" visions: a cleaned-up arcade bustling with bookshops, a courtyard rewilded with native plants, a rooftop café shaded with linen sails.

“The aim is simple. To make ordinary Egyptians imagine Downtown as part of their future. These videos aren’t for architects,” Salem laughs. “They’re for people scrolling at night, people who forgot Downtown even exists."

In a city where heritage is often treated as a museum piece, or an obstacle to new construction, Salem's DIY approach repositions Downtown as something personal, emotional, and ultimately collective.

The story is often recited but rarely truly believed: in the late 19th century, under Khedive Ismail, Cairo’s Downtown was modelled on Baron Haussmann’s Paris. Boulevards sliced through the medieval urban fabric, European architects raised buildings adorned with wrought-iron balconies and Belle Époque mouldings, and cafes bustled with cosmopolitan chatter.

Downtown was not simply Egypt’s administrative centre. It was its cultural, political, and emotional core. But like much of Cairo’s grandeur, Downtown’s golden age proved heartbreakingly brief. The 1952 revolution brought land reforms and the flight of the upper classes. Nationalisation under Nasser fractured property ownership; maintenance budgets evaporated with time.

Over time, balconies sagged, ornate plaster peeled, elevators broke down. Families squeezed into divided apartments designed for another era. Cairo became "a city in a coma" - too burdened by history to move, too battered by politics to heal.

While many now frame Downtown as a brand to be polished or a project to be managed, Mostafa Salem speaks of it the way one talks about a stubborn friend: with exasperation, loyalty, and an intimate acknowledgement of flaws.

“There’s no need to invent a new Downtown,” he tells me. “It’s there. Underneath the cheap tiles, under the fluorescent signs. It’s waiting.”

One building he’s particularly interested in is the Evergreen Tower, a modest, overlooked block that could, with sensitive restoration, become a symbol of the Downtown revival he envisions: affordable, lively, accessible without erasing the past. Salem imagines its crumbling lobby polished back to life, its rooftop turned into a public gathering space, its corridors filled again with foot traffic and informal life.

“We have to work with what we have," he says. "Not against it.”

Salem’s aesthetic is radical in its restraint. "The goal," he says, "is to let the building be itself again." It’s an approach that feels almost revolutionary in a city where speed, spectacle, and shiny surfaces increasingly dominate.

The vision does not stop there. One of the projects Salem is currently working on—in collaboration with government bodies—is the renovation of the Tiring Building, one of Downtown's forgotten giants. Built in 1890, it was once the Middle East’s earliest iteration of a multi-concept department store, decades ahead of its time. Now, the building slouches in near ruin: façades cracked, interiors rotting.

Salem’s first task was deceptively simple: to find the old drawings of the building, and immerse himself in the principles of Baroque architecture. But while blueprints might sit neatly in archives, the reality on the ground was far messier. The Tiring Building, like many Downtown relics, is not government-owned. It belongs to multiple private families and individuals, each holding legal stakes in various sections. Before touching the interiors, Salem had to seek their consent individually, a slow, sometimes Kafkaesque process.

Legally, because the Tiring Building is registered as a protected historical monument , Salem could restore the exterior. Yet when it came to interior work, he had to negotiate piece by piece. The Urban Harmony Committee issues guidelines for preserving such heritage, but their authority is advisory, not coercive: they cannot force shop owners to remove violations like air conditioners, neon signs, or ill-fitting aluminium shopfronts.

“Incredibly, rather than resistance, I found a surprising wellspring of cooperation. Many of the owners, often assumed to be indifferent, welcomed the idea of a rejuvenated Teering Building.” Salem recalls. Salem’s argument was simple but powerful: a restored building would increase foot traffic, cultural prestige, and, ultimately, the economic value of their shops. More visitors meant more business. More visibility meant survival in an era where Downtown risks being abandoned to tourists or forgotten altogether.

“People aren’t enemies of preservation," Salem says. " When you show them what’s possible, and what’s in it for them, they listen.”

Salem’s work unfolds alongside two powerful forces reshaping Downtown Cairo: government-led restoration efforts and private real estate investment. Companies like Al Ismaelia have acquired and restored over 25 historic buildings, reviving landmarks such as Groppi’s patisserie and Café Riche, and drawing renewed attention to the district’s architectural heritage.

Yet even amid this momentum, Salem remains attentive to the question of accessibility, mindful that rising rents and new businesses could gradually shift Downtown toward exclusivity.

Mostafa Salem sees this tension clearly, but he refuses to frame it in simplistic terms. “It’s normal,” he says. “Downtown is part of Cairo’s face to the world. Of course there will be places that target visitors. That’s good. It shows the city is alive.”

His worry is not that tourist cafés or boutique hotels exist—but that they could become the only kind of life left. "If you lose the kiosks, the qahwas, the corner shops—the Downtown we know will turn into a closed compound," he says.

Salem speaks fondly of the old qahwas where workers gather over tea, and the kiosks selling newspapers and cigarettes under faded awnings. "They’re part of us as Egyptians. You can’t plan them into existence. They have to survive naturally."

For him, the healthiest version of Downtown Cairo is one where these layers coexist: visitors drinking espresso in an elegant café beside an old man playing backgammon at a battered table; a restored heritage building standing proudly next to a newspaper kiosk plastered with yesterday’s headlines. A city breathing with all its lungs.

“Order isn’t vibrancy,” Salem says. “You can repaint a façade a hundred times, but if you don’t bring back the people, the noise, the improvisation, it’s dead."

There is no neat ending to this story. But perhaps a more modest hope is possible: not resurrection, but recognition. To glimpse a peeling façade and feel affection, not disdain. To restore a battered balcony not for branding, but so a mother can lean out of it and call her child home.

Working on these projects has shifted Salem’s sense of scale. What began as a handful of restorations now feels like something far larger, and far heavier.

“This has opened a can of worms,” he says. “There are millions of buildings that demand our attention.”

Yet Salem doesn’t see that as a reason for despair. He hopes this work, the stubborn daily negotiations, the drawings, the scraped layers of dust , will open people's eyes to what lies ahead.

“This isn’t the end,” he says. “It’s the beginning of understanding what Downtown, and Cairo, could become.”

Salem is trying to make small acts of attention matter again: a repaired cornice, a reopened stairwell, a building cleared of debris. Tiny stitches in a fabric that can never be wholly mended, and that’s ok. After all, Salem isn’t pretending that he’s saving Downtown Cairo. He’s just trying to help it breathe free and save itself.

- Previous Article Adel Emam to Be Honoured at Fifth Egyptian American Film Festival

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Jan 18, 2026