The Giza Zoo Speaks at ’Darb Fi Al-Hadeeqa’ Art Exhibit

Giza Zoo Collective’s first exhibition with Darb 1718 finds joy amidst the uncertainty of the future, and the past.

Every exhibition opening is a joyful occasion, but the opening night of ‘Darb Fi Al-Hadeeqa’ at Darb 1718 with the Giza Zoo Collective was uniquely so. Amidst the chatter of the audience and artists, it felt like stepping into a shared memory, or—like its name—a picnic in the park with old friends.

"We founded the Giza Zoo Collective a week before the Giza Zoo closed for renovations in 2023," says Fatma Abodoma, a multidisciplinary artist and one of the curators of the exhibition. "The Zoo is a place that holds very good memories for us, but of course when it re-opens it won’t be the same place, and we won’t be the same people. For this exhibition, we had more questions than anything else. We had questions about the zoo, about the changing city, and about our obsession with the past."

"We wanted to move in the direction of having everything in the Zoo speak," says Abodoma. "The trees, the walls, the benches—this was the core concept behind the exhibition, and every artist expressed it in their own way."

The exhibition features 17 artists, eight of whom are with the Giza Zoo Collective or were otherwise invited to showcase their work. An open call for artists was also sent out, and Abodoma, along with co-curators Mohammed Abogabal and Kat Lewis, selected nine applicants out of 200.

United by an undercurrent of nostalgic longing, the exhibited artworks are highly diverse both in medium and approach. As memories, they are expansive and accommodating, even for someone who has never been to Giza Zoo. As works of imagination, they are also thought-provoking. The deft curation, which assigned itself the tricky task of arranging an exhibition about a place that is itself an exhibition, does not shy away from the complex emotions surrounding the Zoo. "Growing older, we become more aware about the harsh reality of zoos for the animals held there in captivity," says Abodoma. "We have wonderful memories, but now we also have more awareness. So how should we feel?"

One of the standout pieces of the exhibition was Tasnim Yousry’s 'Cage', a virtual reality installation with a simple premise: when you put on the VR headset, you are transported inside a small green cage, surrounded by people who are watching you. The execution is excellent, perhaps especially so because of the audio. Yousry used sound bites from her own childhood videos and from videos found on YouTube, and as you are trapped in the cage you can hear the happiness it brings to those watching you. You can hear, for instance, a man remark proudly in Egyptian Arabic, "It was born here in the zoo."

Like most of the other artists, Yousry’s work was inspired by her past visits to the Giza Zoo. "When we were kids, my little sister and I loved being there. We enjoyed the noise and the chaos, and it was my sister who eventually asked, ‘Why are we being happy while the animals are caged?' So I wanted to explore that question, and the wider issue of how we make ourselves happy at the expense of others."

The memories themselves, beyond the ethical questions they raise, are sometimes also bittersweet. Fatma Elzahraa’s Lion, 'Giraffe, Elephant, and Hippopotamus' reconstructs the day after her parents’ divorce, when her mother took Elzahraa and her brother to the zoo, as though telling them that everything was still okay. The artwork is set up like an investigation board: 15 red-hued photographs are arranged on the wall, annotated with handwritten notes and a headphone set that narrates Elzahraa’s work in her own voice. What Elzahraa finds in the photographs—or tries to find—is evidence that the people she and her brother would grow up to become are embedded in that day, all those years ago.

While not all of the exhibiting artists have such intimate memories of the Zoo, nearly all of them have visited it, except one. Mariana Medrano, the artist behind an animated moth projection titled 'Mubarak 3', hails from Mexico. According to curator Kat Lewis, "We had many international submissions, but hers is the only one we accepted. Medrano’s artwork is inspired by a visit she made to the Cairo Agriculture Museum in 2025. It fit the theme well and allowed us to incorporate another relevant institution from Cairo centred around animals."

Medrano draws upon the way the Cairo Agriculture Museum displays its butterfly and moth specimens to spell out different words, such as ‘Mubarak’. Her own seven-minute animation hides within it different messages, albeit in a more layered and ambiguous way. This approach was present in the work of others as well, such as Zahraa ElAlfy’s text-based 'Riddle Me This', and Mariem Akmal’s 'Inferiority Complex'.

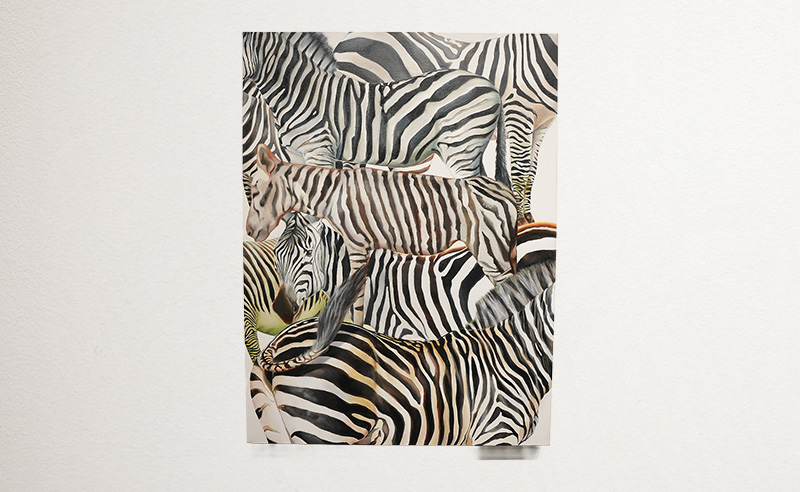

'Inferiority Complex', an oil on canvas work, deceives the eye in two ways. Placed by the curators alongside Brigitte Khouzam’s 'Stillness in Motion', a collection of four photos of cheetahs at the Zoo, Akmal’s painting of zebras appears at first to also be a photo collage. Upon inspection, however, one realises that they are not photographs at all, but the skilled work of Akmal, who has been painting with oil since she was two. Upon even closer inspection, you notice that the zebras are not all zebras. In the centre of the painting is a donkey, painted like a zebra.

Akmal’s inspiration was a viral incident in 2018 when the Giza Zoo painted a local Egyptian donkey to look like a zebra, and put it on display for visitors. "It’s not just about the donkey," says Akmal, "but about our 3o2det el Khawaga, and the extent we’ll go just to try and appeal to the West and conform to their standards."

When Giza Zoo officially opened in 1891, it became Africa’s first zoo, and the third zoo anywhere in the world. Before closing in 2023, however, it had been suffering from decades of neglect, dilapidating facilities, and poor conditions. When the multibillion-pound renovation project was announced, it was hailed by many, but fears still remained over what the new Zoo would look like. Those fears are shared by Abodoma.

"We will always remain nostalgic about the Zoo that was. Will the new zoo have the same impact it once did, before its closure? Giza Zoo was a place that gathered all of Egypt’s social classes in one place. It was a place for families and also, for example, a popular dating spot. Will this continue?" she asks. “We’re not trying to change or improve it—we’re just raising questions and trying to answer them.”

At ‘Darb Fi Al-Hadeeqa’, however, the answers are less important than the questions themselves. They are uneasy questions, and they inevitably place a distance between the Collective and the Zoo it is named after. For Abodoma, the negativity associated with zoos is long past a critical point. “I’m strongly against zoos now, but I kept going to Giza Zoo before it closed because I wanted to document the place. The day of its reopening won’t be a day of celebration for us.”

Rather than finding answers, the exhibition Abodoma, Abogabal, and Lewis have brought to life finds pockets of joy amidst uncertainty—uncertainty over the Zoo’s future as well as its past. Whatever the Zoo may look like upon reopening, they’ll stick to their happy, uncomfortable memories.

The exhibition is on view at Darb 1718 until December 14th.

- Previous Article Egyptian Visionaries on the AD100 2026 List

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026