“Hide Your Face If You Want”: Rehab Eldalil Rethinks Photojournalism

What does it mean to make a photograph without taking one? In this profile of Rehab Eldalil, we explore how the award-winning Egyptian photographer is reframing authorship, visibility, and care.

شوق الغريب للي تقطع سبيله The longing of the stranger whose path has been broken.

The line, taken from a poem by Bedouin writer Mahmoud Abu Hussein, stayed with Rehab Eldalil, award winning Cairo-based documentary photographer and visual storyteller, long after she found it. It described something unresolved, something between memory and distance. Something close to the bone. She had spent years returning to South Sinai, where her great great grandfather once belonged to the Gabaliya tribe, trying to understand how you honour a lineage without claiming it.

Eldalil has spent the past 15 years building a practice grounded in slow, collaborative, community-driven work. Her projects resist extractive photojournalism and centre the ethics of shared authorship.

She is best known for The Longing of the Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken, a decade-long collaboration with the Bedouin community of South Sinai, and From the Ashes I Rose, a multimedia portrait of civilian war survivors across the SWANA region. In 2025, she was awarded the CatchLight Global Fellowship for her work, gaining international recognition for a visual approach that privileges participation over representation, and long-term trust over narrative control. I sat down with Rehab Eldalil over a long video call that moved, like her work, at its own pace.

She spoke with clarity, never performance, circling around questions of power, authorship, and what it means to look without taking. Her daughter Aida made regular appearances demanding mom’s attention from a virtual stranger. None of it broke the rhythm. If anything, it made the point: that care is not separate from the work. It is the work.

Rehab’s grandfather belonged to the Gabaliya tribe, a historically centralised Bedouin group in the mountains of St Catherine. Her father, a veteran of Egypt’s 1973 war, took the family there every year. But even then, the connection felt incomplete. “I was distanced from it,” she tells CairoScene, “but also pulled toward it. I knew I couldn’t speak as a Bedouin, but I couldn’t ignore the ties either.”

That tension would become the structure of her long-form project The Longing of the Stranger Whose Path Has Been Broken, now over a decade in the making. It began with the idea of returning to a place, one she had visited as a child, one rooted into her family history. But it quickly became something else: a practice in decentralising the authorship of the photographer, rethinking representation, and asking harder questions about how a photograph works, and whom it serves. Eldalil didn’t want to document the Bedouin. She wanted to understand how to be in relation to the community without turning them into material. And that meant changing her entire process. “When you hold a camera, you hold power. People automatically become subjects. But in real life, that’s not how stories are built.” Eldalil wanted to make that imbalance visible, and then dismantle it. Instead of simply taking images, she invited the Sinai women to embroider their own portraits. She gathered oral histories and worked with traditional knowledge holders. She allowed the image to be altered, interrupted. “It’s co-authorship.” “They’re not subjects. They’re storytellers.”

A good photograph is not one that wins awards. That much is clear to Eldalil. For her, the only meaningful measure is whether the work honours the agency of the person inside the frame. “They’re not static. They’re not symbols. They’re not representatives of anything. They are storytellers in their own right,” she says. This belief runs through her practice and is implemented through a set of concrete decisions. She builds trust slowly, over time. She doesn’t “Parachute Shooting”; she gives up authorship in visible, often painstakingly long ways. In The Longing, that meant letting go of compositional control. In From the Ashes I Rose, her later work with war survivors in the SWANA region, it meant calling participants to physically transform their own images.

When I ask what that requires from her, she answers without hesitating: “It requires that you know your limits. That you’re not the centre. That your job is not to represent, but to create space.”

From the Ashes I Rose is where Eldalil partnered with Médecins Sans Frontières. They had asked her to document patients recovering from trauma in Amman hospital in Jordan from the SWANA region. She agreed, on one condition: no pity. No reduction of war to visual tropes. “I said, I will not do NGO photography,” she recalls. “I will not turn our people into pity objects.”

The project spanned four months of preparation and 10 days of shooting in the hospital. In the world of editorial photography, that timeline is unusual. Most conflict-related projects are executed in days, sometimes hours, driven by news cycles and the pressure to produce dramatic imagery.

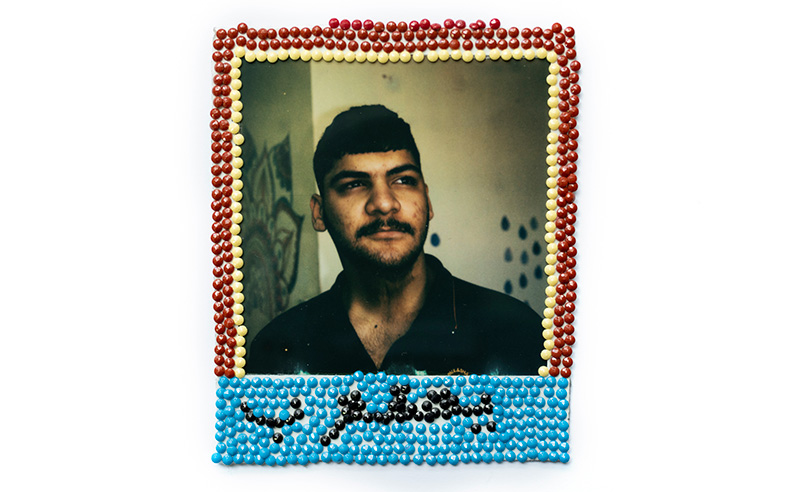

Eldalil’s work resists all of that. Instead, she asked survivors what they liked. What made them feel calm. She used polaroid photography to take their portraits and asked them to “destroy” them, mark them, thread them, cover them with stickers or beads, or, if they chose, to hide their own faces if they want to. She spent those 10 days simply being present: listening, asking what colours they love, what memories felt safe to hold. The word she used ‘destroy’ wasn’t careless. It was liberating. In a medium that has so often stolen agency, destruction became a form of authorship.

Patients altered their images with diamond painting, a craft used in art therapy workshops that involves placing tiny resin tiles onto adhesive patterns. Diamond painting was already a familiar activity in the hospital, used by the mental health department as part of art therapy sessions. Its repetitive, tactile nature helped patients manage anxiety and focus their attention, while its low-stakes creativity offered a sense of calm and control. These mosaics, made by the participants themselves, became the layer on top. The photograph was the backdrop. Some participants covered their own faces. Others left them visible. In fact, two of the participants who planned to cover the faces decided not to in the end because they felt that sense of authorship.

“There’s a freedom in honouring how people choose to be seen,” Eldalil says. “Or not seen.”

In this photograph, Shams, a young girl from Baghdad, rests on the lap of her mother, Noura A. When Shams was just two years old, an explosion altered both their lives: Shams suffered injuries to her face, neck and hands, while Noura sustained damage to her hands while trying to protect her daughter. Shams has since lost partial eyesight and hand mobility. The image is simply the quiet intimacy between a daughter and her mother - exactly what Eldalil intended or not intended it to be.

“I saw my own family in them,” she says. “I’m a mother too. You stop seeing ‘subjects’. You start seeing lives.”

Many thought the project timeline was excessive. Eldalil doesn’t. “You cannot build trust on a deadline,” she says. Eldalil’s commitment to slowness is ethical. It is about undoing the mechanisms of visual extraction that structure so much of global photography, particularly when it comes to the Middle East. “I lived in the US during 9/11,” she tells me. “I saw the way we were turned into categories. Our complexity is erased. That reduction doesn’t just happen in headlines. It happens in images first.” Her resistance to that flattening runs deep. And it comes with a critique, not just of Western audiences, but of Arab photographers too.

“We’ve internalised it,” she says. “We’ve learned how to frame ourselves through other people’s expectations.” It gestures to what Frantz Fanon called the “epidermalisation” of colonialism, the way external judgement becomes internal truth. In psychological terms, it’s a kind of aesthetic learned helplessness: when even representation feels pre-scripted, we stop trusting our own gaze.

Eldalil’s response is not just to change who holds the camera, but to question what the camera has already taught us to see. She doesn’t just want more Arab photographers. She wants Arab photographers who unlearn the visual habits of dominance, who can see beyond pity, tragedy, or strength as performance. “Even when we’re behind the lens,” she says, “we sometimes repeat the same visual codes.” I ask her directly: What does it mean to be a good photographer? El Dalil talks about responsibility. “A good photographer is someone who listens more than they shoot. Someone who leaves space for silence. Someone who accepts that they are not the best person to tell every story.”That last point is crucial. She believes too many photographers assume that proximity equals permission. That being “from the region” grants access. “It doesn’t,” she says. “You still have to ask. You still have to earn it. And you still have to be willing to get it wrong.”

In 2025, Eldalil was awarded a CatchLight Global Fellowship. The grant, given to visual storytellers who centre community engagement, will help fund the second phase of From the Ashes. The first phase of the exhibition was a commission from MSF and Cortona on the Move festival and was staged at the festival in Italy in July 2024 and in Milan in November 2024. Visitors were invited to respond in writing. Over 1,000 notes were collected. “Stop war now” appeared again and again.

The fellowship gave her visibility, but more importantly, it gave her access to an audience that rarely sees work like this on its own terms. “It’s a Western institution,” she says, “and that was part of the value. Because From the Ashes I Rose needed to reach a Western audience, an audience often unaware of what’s happening in the SWANA region, and of the violence their governments have helped sustain.”

In that sense, the project becomes more than documentation. It becomes a tool - a call to action, directed at the very systems that have long shaped how suffering is distributed, and how it’s seen. She is now entering the second phase of the project, with more freedom and more time. She will follow up with participants. Return to the same families. Expand the diversity of the stories. “Now I get to work into the complexity,” she says. “To let things evolve.” What binds both of her projects is a commitment to reframing not just the image, but the image-maker. Eldalil doesn’t see herself as a narrator. She’s not “giving voice.” She’s not explaining a culture. She’s creating a room. And if that sounds passive, it really is the opposite.

- Previous Article WATCH: This Ancient Egyptian Site is Officially Out of Danger

- Next Article Foreign Ownership in Saudi Market Rises 501% Over Eight Years