This Southern Saudi City Is Where Faith Was Forged in Fire

Najran’s towers and ditches hold the trace of trade, massacre, and belief that shaped the region’s memory.

Originally Published June 21, 2025

In the far south of Saudi Arabia, where the mountains taper into a great and scorching plain, there is a city that appears almost by accident, wedged between the highlands of Asir and the empty immensity of the Rub’ al Khali, the Empty Quarter—Najran.

There, the road curves through flat-bellied valleys and dips into thick groves of date palms. Occasionally the land flashes a scatter of low stone buildings or mud-brick towers—and then nothing again.

Najran is not a large city, nor a particularly loud one. Its charm comes from its ability to carry an old weight, the kind one finds underfoot, in the grain of the walls, and in the dusted glaze of the pottery unearthed from its soil. People have passed through here for over four thousand years: traders with incense caravans, missionaries on foot, kings with gold rings heavy on their hands. It is not the end of the world, though it may evoke the sensation of being at the edge of it.

South of modern Najran, behind a fenced archaeological site and a flat expanse of sand, sit the crumbling outlines of Al-Ukhdūd. Not ruins in the traditional sense—there are no tall columns or sprawling mosaics in sight—but a boxy, haunted emptiness. The walls, square and thick, stretch to about 220 meters in one direction, 230 in the other. They enclose a city that has been cut and re-cut into the land: streets, cemeteries, shattered foundations, and the curved edges of watchtowers now melting into the earth. Bronze objects have been found here. Glass beads. Pottery that still holds the burn of its last fire. But it is not the artifacts that give Al-Ukhdūd its charge. It is something darker. To find it, one need only to turn to its history.

Sometime in the early 6th century CE, the Himyarite King Dhu Nuwas is said to have carried out a massacre here. Christians, by the hundreds, burned alive in a trench—"the People of the Ditch," as they are remembered in the Qur’an. The earth, disturbed and disturbed again by archaeologists, gives back layers of history that don’t align so much as collide: pre-Islamic temples, Christian chapels, Islamic inscriptions etched long after.

There is no single story to Najran. Just a chorus of ghosts.

Long before the Prophet Muhammad received the Christian delegation from Najran—one of the first recorded interfaith encounters in the region—the city had been a pilgrimage site. A Kaaba once stood here. Not the Kaaba, but a local one, sacred and central to the communities that worshiped before Islam took hold. Dhu Nuwas razed it. The Aksumites, Christian invaders from across the Red Sea, built it again.

Religion in Najran has never been fixed. It has changed hands, changed names, left scars. But the memory of faith here is thick. It cannot be washed away by time.

In the Old City, the buildings stand pressed together, cautious and close like villagers around a fire. Three and four stories high, made of clay and wood, they lean slightly inward. The walls are a deep mud colour, flecked with sun-whitened wood. Latticework windows let in light but guard against heat. Doors—some carved, some simple—bear marks from decades of use. Narrow streets run between them, dusty veins that open onto courtyards, hidden rooms, stairwells. Most of these houses are watchful. They’ve seen too much to be otherwise.

There are two palaces worth noting. Al-Aan Palace, perched on a low hill, watches over Najran with a stern and quiet face. Built in 1688, it’s made from the same earthen palette as the homes below it but stands apart, four stories tall, its edges sharp against the horizon. From its roof, one can see the whole valley, the way a falcon might. The second, Emarah Palace, is less dramatic but no less important. Built in 1944 as a seat of government, its thick mud walls and squat towers remind visitors that even bureaucracy, here, has a kind of architectural grace.

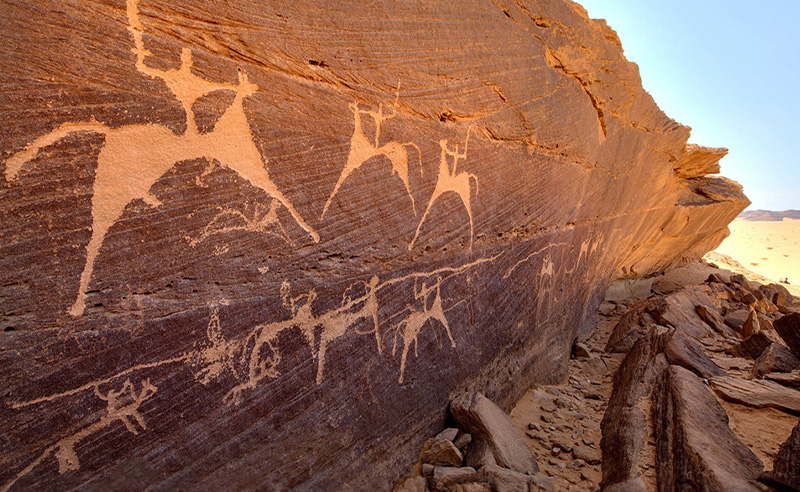

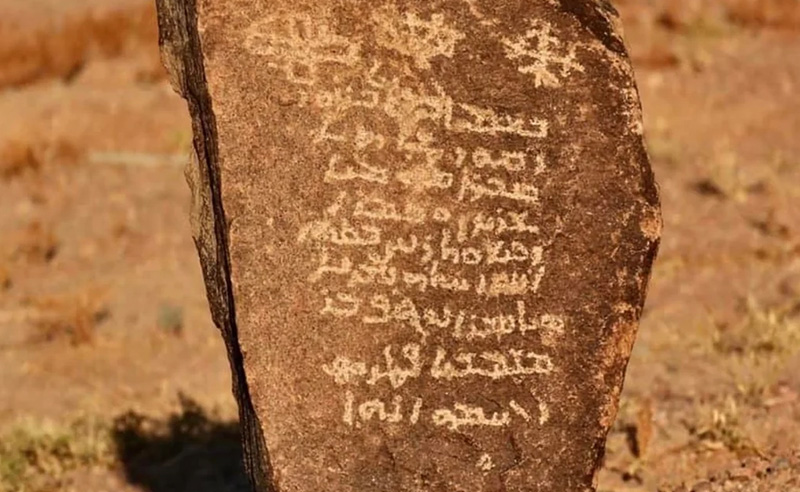

But Najran is not only a city of buildings and ruins. Drive out past the far edges of town, where the hills begin to rise and the brush grows sparse, and you reach Bir Hima. A rock art complex now recognized by UNESCO, it spreads thinly across the landscape with thousands of inscriptions, petroglyphs, and ancient doodles carved into the stone. The earliest date back to 7,000 BCE. Camels, warriors, ibexes, rituals. The scripts—Musnad, Thamudic, Aramaic, early Arabic—layer over one another like graffiti in a stairwell, each one a mark of presence. This is where stories were first scratched into permanence. Where someone, long before modern language, tried to say: “I was here.”

Today, Najran balances uneasily between past and present. Its museum—a regional institution filled with archaeological finds and interpretive displays—tries to thread the pieces together. The restorers patch the palaces. The scholars take notes. And yet, some buildings still crumble. Some roads still lead nowhere. Preservation is never perfect. But it is something. A gesture toward remembering and not letting the layers be lost.

What makes Najran feel so different is not that it is old—many cities are old—but that it remembers. Even its silence feels crowded. With merchants from Yemen. With missionaries from Ethiopia. With kings, prophets, and poets. With the heat of the ditch and the prayers of the faithful. It is a city on a border, not just of nations, but of faiths, climates, and time itself.

- Previous Article This Agency is Turning Prom Nights Into Full-Scale Productions

- Next Article Where Weave Meets Wheels: Kahhal 1871’s New Visual Statement

Trending This Week

-

Jan 18, 2026

-

Jan 18, 2026