Doha's New Museum Brings a Self-Exiled Artist’s Vision to Life

From towering canvases to multi-sensory installations, the M. F. Husain Museum in Doha brings to life the journey of an artist whose career spanned continents, mediums, and decades.

When walking through the galleries of the new Lawh Wa Qalam: M. F. Husain Museum in Doha, the first thing that hits you is the sheer volume of work. More than 150 pieces across painting, film, and sculpture make it clear that this is not simply a retrospective, but the first museum in the region dedicated to a single modern artist, built to capture the force of his creativity and the global arc of his life. A life that ended in self-imposed exile in Qatar after controversy over a handful of provocative depictions of deities.

The museum, now open in Education City, centers Maqbool Fida Husain, one of India’s most celebrated—and contested—modern artists. A founding member of the Progressive Artists Group established in Bombay in 1947, Husain helped redefine Indian modernism through his eclectic approach to form, colour, and narrative. His career unfolded across decades and continents, making a museum of this scale not only appropriate but necessary.

A short introductory film charts the trajectory of his life. Born in 1915 in Pandharpur to India’s Muslim minority, Husain experienced early loss when his mother died before he turned two—a personal rupture that would echo in his lifelong interest in maternal figures. His rise to prominence in the 1950s anchors the first gallery, 'A World of His Own,' where towering canvases in saturated colour illustrate the energy and ambition that defined his early work. His own words guide the curatorial spirit: “When I begin to paint, hold the sky in your hands as the stretch of my canvas is unknown to me.”

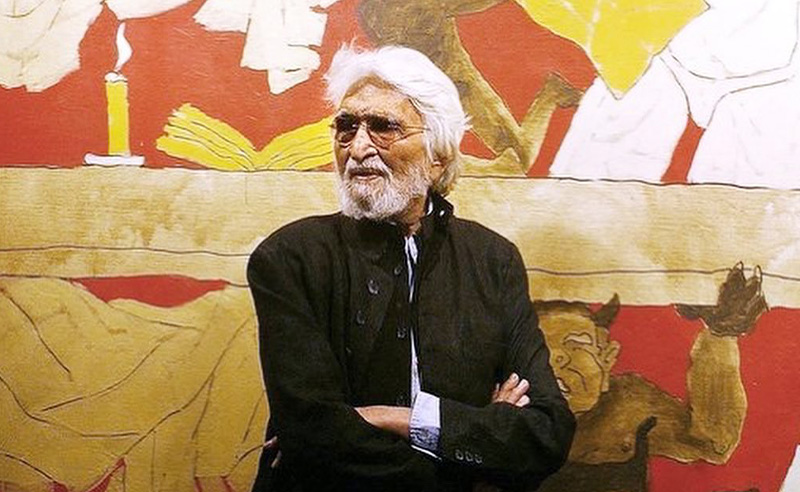

Works like 'Quit India Movement' link him directly to the history of anti-colonial struggle, while a surrounding film tower immerses visitors in Bollywood sequences that highlight his influence beyond traditional fine arts. At the height of his fame, his imagery spread across airports, convention centres, billboards, calendars, and living rooms across India. His appearance—white hair, round glasses, and bare feet—became as iconic as his brushstrokes.

The second gallery turns to Husain’s intellectual and spiritual dimensions, assembling books written about him, magazine covers, and black-and-white portraits that reveal the idiosyncrasies of his character. Here, Husain appears barefoot with a brush in hand, crouched in zigzag poses—an embodiment of creative restlessness. The space conveys not just the evolution of his style, but the evolution of his thought.

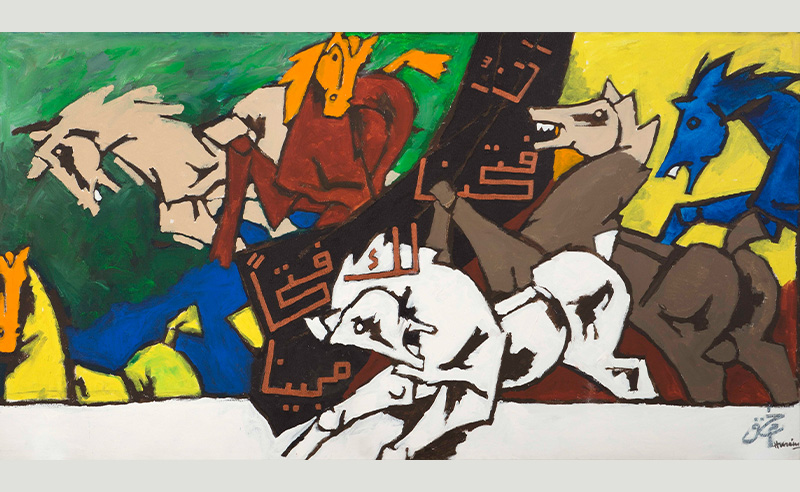

The third gallery focuses on Husain’s final decade, spent largely in Qatar. Central to this section is the Arab Civilization Series, commissioned by Her Highness Sheikha Moza bint Nasser. The works revisit defining moments in the region’s history, from the Battle of Badr to a triptych uniting Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Together, they articulate Husain’s belief in a shared cultural and spiritual lineage, a theme that shaped much of his late work.

Alongside 35 completed paintings, the gallery introduces 'Seeroo fi al Ardh,' the multi-sensory installation that Husain began in Qatar but did not live to finish. Housed in a dedicated structure next door, the kinetic display animates crystal horses and rising automobiles within a choreography of sound and light—an allegory of humanity’s journey from nature to machine.

To understand how Husain arrived in Qatar, the museum traces the controversy that pushed him into self-exile. Known for his portrayals of women—goddesses, mythological archetypes, and symbolic figures—Husain became the target of hardline Hindu nationalists in the 1990s for nude depictions of deities. Court cases and increasing threats forced him to leave India in 2006. Arriving in Doha the following year, he was later granted honorary Qatari citizenship in 2010, a distinction rarely afforded to foreigners. He died in 2011 at the age of 95.

Museum curator Noof Mohammed emphasizes that many works created during his time in Qatar had never been shown before, a fact that shapes the structure and intimacy of the final gallery. The exhibition reflects a mutual relationship: a country offering refuge to an artist in exile, and an artist offering a vision of unity, multiplicity, and cultural dialogue.

By dedicating a museum to an artist born outside the Arab world, Qatar expands the parameters of what constitutes “regional” art. The M. F. Husain Museum reframes the region through its long-standing, often overlooked connections to South Asia—shared traditions, languages, aesthetics, and the lived contributions of a large South Asian community woven into Qatar’s cultural fabric. In doing so, it challenges inherited colonial boundaries that once dictated which narratives belonged to the “East” and who had the right to define them.

The building itself reinforces this ethos. Designed by Delhi-based architect Martand Khosla, the museum is based on a 2008 sketch Husain drew shortly before his death. Translating an artist’s drawing directly into architecture required abandoning conventional rules. “It was as if I was having a conversation with him beyond the grave,” Khosla shares with SceneTraveller. “He left clues in the drawing about who he was and how he thought.”

Lawh Wa Qalam—'The Canvas and the Pen'—encapsulates Husain’s belief in art as a tool for exploration. The museum does not close the final chapter of his story; it opens a new one. In Doha, Husain’s work becomes part of a continuing conversation about belonging, identity, and how far a canvas can stretch—beyond borders, beyond disciplines, and beyond the limits of any single narrative.

- Previous Article Riyadh Mood Launches First Riyadh Season Record

- Next Article How Egypt is Boosting its Airports via Public-Private Partnerships