A Beiruti Breeze Sparked Tala Barbotin Khalidy’s New Hawa Collection

Khalidy works with Lebanese and Syrian artisans, reviving endangered techniques through pieces meant to be lived in, not preserved as static artifacts.

‘A CELEBRATION OF CULTURE TO NOURISH THE MIND, BODY, AND SOUL’

This is the first thing you see when you land on when you browse Tala Barbotin Khalidy’s website, and it truly gives you a feeling about her entire world all distilled in one sentence. Khalidy’s design philosophy does not come from a factory perfect place, but rather from memory, travel, family, and craft. Levantine regions that have seen difficulty and beauty, sometime at the same exact time.

Her latest collection, Hawa, came from a deeply personal place. "It was after a period where I felt really isolated, and not inspired creatively because of the war in Lebanon," she tells SceneStyled. Then a ceasefire came. Leaves fluttering and blowing as if with a breath and a tiny window of breeze. “I was literally on my balcony in Beirut… the wind felt really nice.” That small, ordinary sensation opened the door. “That literally sparked the idea.” Khalidy was born and raised in Paris, but has roots in Lebanon and Syria. Each of these three identities is more like a piece of fabric woven from three spools of thread, all together, each adding something.

Khalidy was born and raised in Paris, but has roots in Lebanon and Syria. Each of these three identities is more like a piece of fabric woven from three spools of thread, all together, each adding something.

“I grew up in Paris," Khalidy says, "which was a huge influence in terms of style, a lot of kind of more effortless, toned down style. But then in contrast, with my Lebanese and Syrian heritage, I had access to a lot of really rich textiles and fabrics and also ornaments, embroidery, crochet, craftsmanship."

Her approach to design incorporates the calm every day pieces she grew up seeing in Paris and the deep textures and heritage that comes from experiencing Lebanon and Syria. Khalidy decided her mission early on during her thesis at Parsons, Fashion Institute of Technology. "I did my thesis on embroidery as a identity," she says, "Identity as an occupational craft, and as a construction method, and I really dove into endangered techniques and how those techniques relate to cultural identity."

Khalidy decided her mission early on during her thesis at Parsons, Fashion Institute of Technology. "I did my thesis on embroidery as a identity," she says, "Identity as an occupational craft, and as a construction method, and I really dove into endangered techniques and how those techniques relate to cultural identity."

Two years later when she began her brand, with her mission already the backbone: working with artisans in Lebanon and Syria, holding space and giving voice to techniques that were disappearing, and letting these crafts exist in clothes meant to be worn, meant to live on the body, not be frozen in amber.

"The mission is to work with Lebanese and Syrian artisans, to revitalize local crafts, and textiles from that region, that are contemporary ready to wear pieces." Khalidi is not making couture or fantasy pieces, just clothes that real people can wear to real places. "The Maya skirt is a perfect example: a silk maxi skirt made with Syrian silk from Damascus. Flowing. Pin tucked by hand. Unique yet familiar enough to wear anywhere. Our silk comes from a fabric merchant in Damascus. He’s in his eighties now and he used to work with my grandmother."

"The Maya skirt is a perfect example: a silk maxi skirt made with Syrian silk from Damascus. Flowing. Pin tucked by hand. Unique yet familiar enough to wear anywhere. Our silk comes from a fabric merchant in Damascus. He’s in his eighties now and he used to work with my grandmother."

There’s beauty in Tala’s work, but also the everyday difficulty of creating in Lebanon, and she is open about this part as well. "You know whenever there is any kind of political unrest… when there was war last winter we had to rethink our production," she says. Gas shortages, closed borders, artisans physically unable to leave their homes...clothing is no longer a piece of fabric when the world is shaking around it.

And then there is the perception problem; some people still perceive Middle Eastern crafts as "less refined," as she puts it, or unstable. She learned not to respond with defensiveness but with proof, the research, the history, the many hours of labor behind each piece of clothing. "I always want to represent the work that we're doing and the artisans in a really positive light."

Khalidy is always planning ahead in order to survive the unpredictability, stocking fabrics when borders shift, adjusting timelines, finding creative routes, etc.

She even leads workshops in embroidery so customers can repair or prolong the life of their pieces.

Hawa, Khalidi’s latest collection is a tribute to air, softness, and recovery. Easy silhouettes, airy fabrics. It doesn't weigh heavy even when that inspired history is deeply rooted, rather it almost feels as if you can breathe heritage into it without it being ceremonial or heavy. While other designers might respond to trauma with dark brutal work, Khalidy chose ease. She took cues from dervish spirals and the movement of traditional Persian tiles, gardens painted in blues and golds, spiraling clouds, and mythic animal motifs blending spirit, nature, and love. Referring to whirling dervishes connects to devotion while serving as a vortex of air, hawa as spiritual motion, with traditional Persian panels of lovers separated by landscape transported by wind, birds, and fate. She also pulled color and emotional clues from Fairuz’s Nasam Alayna El Hawa, screenshotting scenes of sea-blue horizons, Fayrouz’s red scarf, and longing to construct her palette. And for the first time she worked with silk scarves from Aleppo, all of which contained motifs that were not often seen in the current fashion.

She took cues from dervish spirals and the movement of traditional Persian tiles, gardens painted in blues and golds, spiraling clouds, and mythic animal motifs blending spirit, nature, and love. Referring to whirling dervishes connects to devotion while serving as a vortex of air, hawa as spiritual motion, with traditional Persian panels of lovers separated by landscape transported by wind, birds, and fate. She also pulled color and emotional clues from Fairuz’s Nasam Alayna El Hawa, screenshotting scenes of sea-blue horizons, Fayrouz’s red scarf, and longing to construct her palette. And for the first time she worked with silk scarves from Aleppo, all of which contained motifs that were not often seen in the current fashion.

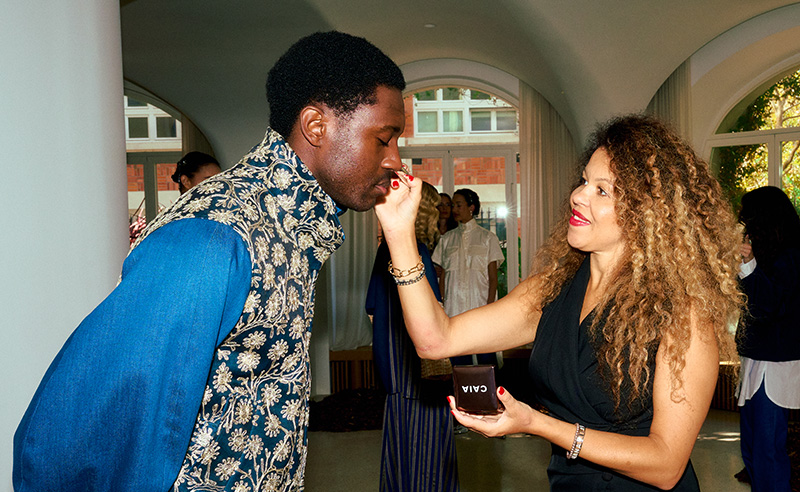

This year marked Barboutin's debut exhibition for Paris Fashion Week, it was not show on a runway, but rather a more intimate presentation. Instead of rushing across the runway under bright lights with bright and colorful pieces, each person walked through slowly, at a pace more contemplative and thoughtful rather than frantically to see what the next model would look like.

People walked through and had conversations with Khalidy, they actually could see and connect to the work up close to examine attention to detail, and craftsmanship. "It was honestly super lovely," she explained. "The idea was just to have a space where people could come hangout, meet each other, and get to know the clothes, and not have models walk down a runway and everyone just kind of leave." She created a spiral walkway lined with pine bark, some blood orange-colored drapery, a nod to the idea of wind. Visitors walked slowly, asked questions, and accepted the creative journey to get there. People told her and her team it was a nice slow break in the middle of all the business of Fashion Week.

She created a spiral walkway lined with pine bark, some blood orange-colored drapery, a nod to the idea of wind. Visitors walked slowly, asked questions, and accepted the creative journey to get there. People told her and her team it was a nice slow break in the middle of all the business of Fashion Week.

Hawa taught Khalidy what to be aware of in terms of what people were responding to, she is also eager to explore even further; especially the repetition of techniques she developed with her last collection for the new scarves. But more fundamentally, she wants to find ways to create spaces to meet in community with people about fair trade practices; in pop up events in London, Beirut and beyond. "Really being more community centered," she says. “That is the goal.”

Khalidy still dreams and plans to dive into more authentic practices, "Metal embroidery," she says, really a craft of bending and shaping real metal as a craft. "It is a metal-thread embroidery craft, only a few artisans can still do it."

Trending This Week

-

Dec 23, 2025