Alaa Awad’s Neo-Pharaonic Murals Unleash What Tourists Queue to See

From Luxor’s temples to Cairo’s streets, Awad paints goddesses, battles and processions that collapse millennia into the language of now.

What politics unsettles, art absorbs; revolutions pulse first in the streets, then in the studios. In fin-de-siècle Vienna, the artists of the Secession movement, Gustav Klimt amongst them, broke from the academy to dismantle the ornate certainties of art nouveau. They painted walls with political tremors; Beethoven’s tragic chords set into plaster, gilded friezes that carried the upheavals of their own society. Alaa Awad remembers discovering this history while studying in the arts faculty in Zamalek, tracing the way politics could carve itself into aesthetics and art. For him, it was a revelation: revolutions leave not just monuments or slogans, but murals. They literally seep into walls.

Today, Awad is a practising artist and a scholar: he holds a PhD in Fine Arts and serves as an assistant lecturer in the Department of Mural Painting at South Valley University in Luxor, one of the few places where the discipline is still formally taught. There, he guides students through the challenges of a craft with dwindling commissions and even fewer public walls to claim. Yet he insists on the urgency of training young artists in the lineage. Each mural, he tells them, is part of a continuum. The line runs from Karnak to Mohamed Mahmoud, from the friezes of Ramses to the brushstrokes of 2012. “I wanted to channel heritage into contemporary mural arts,” he tells CairoScene. In Awad’s vision, the wall is both fragile and eternal. Paint fades, plaster peels, gets whitewashed. Yet the act of painting, of carrying brushes to a wall, of arranging processions and animals and women in sequence, places the present inside a lineage thousands of years long.

Awad has been drawing on walls, in his own way, since adolescence. Born in Mansoura in 1981, he spent his early years between the Delta and Cairo before enrolling at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Luxor in 1999. Luxor held him in place: the landscape, the Nile, the silence of temples, Awad saw it as a living archive. As a teenager, he would carry sketchbooks to the colonnades, drawing by hand the reliefs and processions carved into sandstone millennia ago. The first peace treaty in recorded history - the Battle of Kadesh carved at Karnak - was a historical lesson and a visual one that taught him what walls could preserve.

“I liked the idea of documentation,” he recalls. “I wanted to truly see Luxor and live it.” His teachers encouraged him. He recalls that ever since he was a kid, he was filling pages with animals, festival scenes, the October war victories that still hung heavy in public iconography.-77712f4d-b1b4-4df0-be5d-d8efb71f8b86.png)

If Luxor’s walls offered antiquity, Awad’s imagination wandered further afield with Egyptian modernists holding him firmly - Hussein Bicar, Ragheb Ayad, Gazbia Sirry. Trips to the Museum of Modern Art in Cairo introduced him to canvases by Georges Sabbagh, Hamed Nada, and other artists who had pulled pharaonic silhouettes into the 20th century.

During summer breaks, he joined a consulting bureau at his faculty that worked in reconstruction of murals. It was practical labour, scaffolds, cement, restoration, but it gave him his first sustained encounter with mural painting. They were images writ large, public, declaring epics and battles on walls. He was fascinated by their collective function, their role in documenting social consciousness. By the time he returned to Luxor each semester, he knew his discipline: mural painting.

If Awad’s beginnings were archaeological, his break into visibility was revolutionary. In 2012, amidst the clashes around Mohamed Mahmoud Street off Tahrir Square, he painted his first mural. Cairo was raw with grief, the Port Said stadium massacre had left more than 70 dead, the political future was unsettled, and walls had become repositories and canvas for mourning. Awad arrived with brushes and acrylic paint, not spray cans, and began work on a vast procession of women: veiled, unveiled, upright, their eyes steady. The piece became known as 'Al-Hara’ir' ('The Free Women').

“The women were not martyrs or icons; they were continuities, stepping from pharaonic reliefs into contemporary Cairo.” As if the goddesses of Luxor’s tombs had returned to the surface, to bear witness to modern day Egypt.

The mural did not last; few did. Mohamed Mahmoud’s walls were painted over, repainted, painted over again. But for Awad the impermanence was part of the charge.

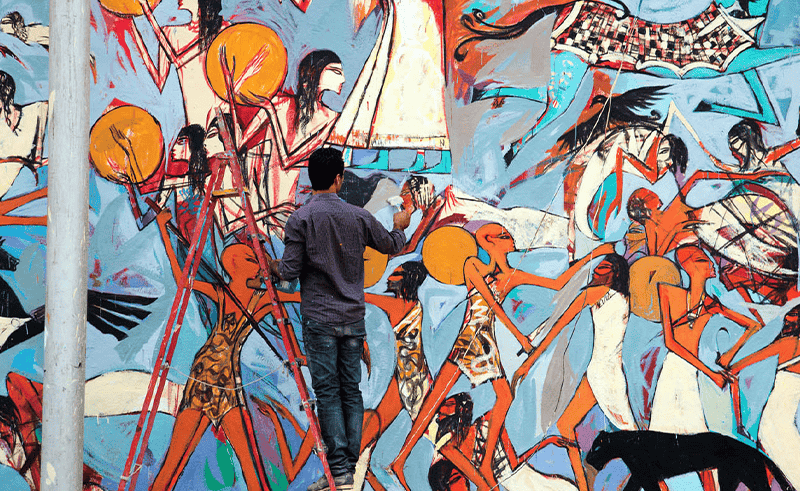

Awad’s critics call his style neo-pharaonic. He extracts motifs–the cat serving a mouse on a limestone wall, the ordered chaos of Kadesh battle scenes, the rhythmic engineering of temple friezes - and transfers them into a present tense. His processions resemble those at Medinet Habu, but the faces echo Cairo’s own.

In his hands, the visual language of antiquity becomes not museum artefact but street language.

His technique departs from the shorthand of contemporary graffiti. Awad paints with brushes, layering acrylics in ways closer to academic fresco than to spray tags. That slowness allows detail: hands clasping, anklets glinting, the subtle tilt of an eye. For him, each mural is both homage and intervention, proof that ancient Egyptian art can be modernised without distortion.

After Mohamed Mahmoud, Awad’s work began travelling. Murals in Massachusetts, in France, in Munich, carried his neo-pharaonic idiom beyond Egypt. Yet the core remains the same. Whether painted on a Luxor wall or a Bavarian museum, the murals speak in a language he first heard as a boy tracing hieroglyphs with pencil and pen.-d647ef70-3190-406a-adf6-dd44e4e08152.png)

Among the works abroad, one of his favourites is Justice, a sixty-foot mural in North Adams, Massachusetts. Winged figures derived from the goddess Maat hover above processions, chariots in motion. Yet his heart returns to Cairo. “My favourite,” he admits, “is 'Al-Hara’ir'.” The Free Women remain the mural where art and revolution, history and present, met with full force.

- Previous Article The SceneStyled 'Texture Index' Edit

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Jan 25, 2026