‘Minister of Tut’: The Man Who Saved Tutankhamun's Treasures

Morcos Pasha's actions ensured that the full contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb remained in Egypt, paving the way for their display in the Grand Egyptian Museum a century later.

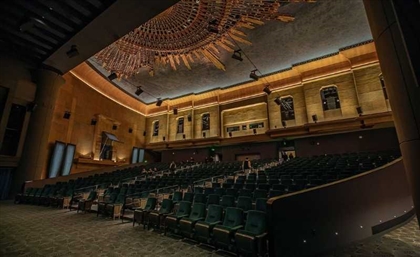

Inside the halls of the Grand Egyptian Museum, the full contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb—over 5,500 artefacts—are now being disayed together for the first time. As Egyptians celebrate this momentous occasion, one person in particular is owed credit: Morcos Hanna Pasha, the ‘Minister of Tut’, whose efforts to prevent the theft of Tutankhamun’s treasures under British colonial rule made such an achievement possible.

The discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, one of the most consequential discoveries of the 20th century, is a story that often revolves around one name: Howard Carter. In 1922, while leading excavations at the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, Carter’s team found the legendary tomb, opening it for the first time since it had been sealed 3000 years ago.

Recent retellings of the story, however, have sought to also recognize the Egyptians who were instrumental to finding—and preserving—Tutankhamun’s treasures. One of these was a young boy from Luxor named Hussein Abdelrasoul. Morcos Hanna Pasha, an Egyptian nationalist and politician, was the other.

Working on the excavation site under Carter’s team, Abdelrasoul was carrying water to the labourers when his donkey stumbled and fell. By chance, Abdelrasoul noticed that beneath the wet sand a stone step had been carved into the ground, and he quickly called for Carter. Carter ordered an excavation of the spot that had for years been eluding his team, uncovering first the staircase and eventually the tomb that would spark a wave of Egyptomania across the world.

As these events unfolded, Marcos Hanna Pasha was sitting in jail, awaiting his execution. Hanna, who was part of the nationalist Wafdist party of Saad Zaghloul at the time of the latter’s exile from Egypt, had been sentenced by an English military court under the charge of printing publications that would incite public hatred for the British-controlled Egyptian government.

However, the government that charged Hanna fell before his sentence could be carried out, and under the new government that replaced it—led by Saad Zaghloul upon his return to Egypt—Hanna was not only freed from prison but given a post as the Minister of Public Works in 1924.

It was Hanna’s fortune that matters related to archaeology and antiquities fell under the purview of his ministry. Since its discovery two years prior, several matters relating to the excavation of the tomb led to controversies surrounding Howard Carter and his British financier, Lord Carnarvon. They had been suspected by many within Egypt and elsewhere of keeping artefacts from the tomb for themselves. (Lord Carnarvon, who insisted he was owed the rights to half of the contents of the tomb for having funded its excavation, did little to ease the suspicions.)

Soon after Morcos Pasha became the minister, Carter invited his British team and their wives to privately view the tomb, whilst at the same time obstructing Egyptian officials and the press from accessing it. Enraged by what he viewed as an insult not only to him but to all Egyptians, Hanna took the decision to close off the tomb. The keys were to be taken from Carter and handed over to the Egyptian government, and police were dispatched to protect the site and ensure that its contents were complete. For this, Hanna was celebrated in the streets of Egypt and hailed by the cheering masses as the ‘Minister of Tutankhamun’. Carter, meanwhile, was branded a thief. Although Carter would eventually be granted permission to complete the excavation, this stand-off between him and Hanna became a microcosm of the greater struggle between the Egyptian movement for independence and British domination of the country’s affairs. Hanna’s actions ensured that the full contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb remained in Egypt, paving the way for their display in the Grand Egyptian Museum a century later. They also demonstrated to a stirring Egyptian populace that independence from colonial rule meant not only seizing back control of the country’s future, but also of its past.

Although Carter would eventually be granted permission to complete the excavation, this stand-off between him and Hanna became a microcosm of the greater struggle between the Egyptian movement for independence and British domination of the country’s affairs. Hanna’s actions ensured that the full contents of Tutankhamun’s tomb remained in Egypt, paving the way for their display in the Grand Egyptian Museum a century later. They also demonstrated to a stirring Egyptian populace that independence from colonial rule meant not only seizing back control of the country’s future, but also of its past.

- Previous Article Cinematic Season Style Guide with GFF's Salma Malhas & Hayat Aljowaily

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026

-

Feb 03, 2026