Jordan's Qusayr ‘Amra is Where Stone & Sky Conspired to Make a Palace

Qusayr ‘Amra may look like a simple desert outpost, but inside lies an 8th-century Umayyad retreat painted with hunters, musicians, kings, and one of the earliest zodiac domes in Islamic art.

Spread across the baked plains of Jordan’s eastern desert stands a structure that reveals almost nothing of its brilliance at first glance. Qusayr ‘Amra—built in the early 8th century during the reign of the Umayyad prince Walid ibn Yazid (who would briefly become Caliph Walid II)—appears, from afar, like an abandoned outpost. Low and earth-coloured, its limestone blocks nearly melt into the horizon.

But the modest exterior is only camouflage.

Slip past the threshold and you enter one of the most extraordinary architectural survivors of the early Islamic world—a pleasure pavilion, a royal bathhouse, and a private retreat set deep in the emptiness of the steppe.

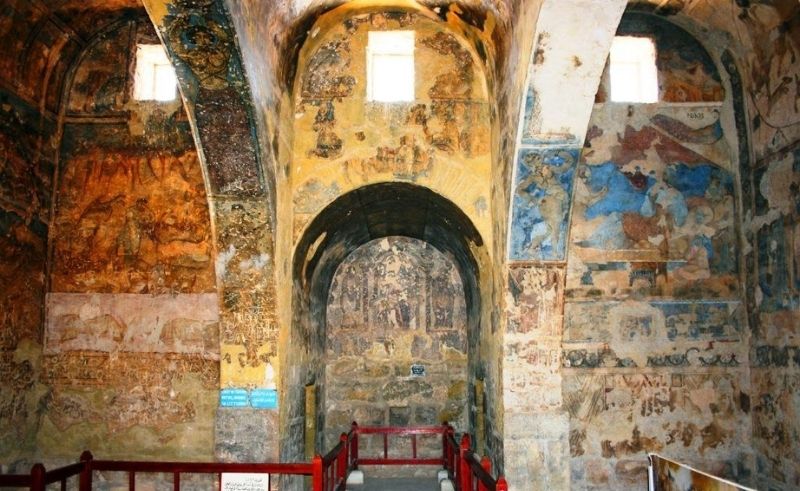

The plan of Qusayr ‘Amra is deceptively sophisticated. To the west, a rectangular audience hall rises beneath a series of barrel and groin vaults. To the east, a complete hammam complex unfolds, modelled on Roman and Byzantine bathhouse traditions yet adapted to the desert context: a frigidarium, a tepidarium, and a caldarium, each heated by a precisely engineered hypocaust system fed by a furnace room.

Its builders worked with local limestone and basalt, shaping thick walls to trap coolness during the day. Small apertures punctuate the vaults; slivers of light that turn the rooms into softly glowing caverns. Everything is scaled for intimacy, crafted not for public crowds but for private indulgence.

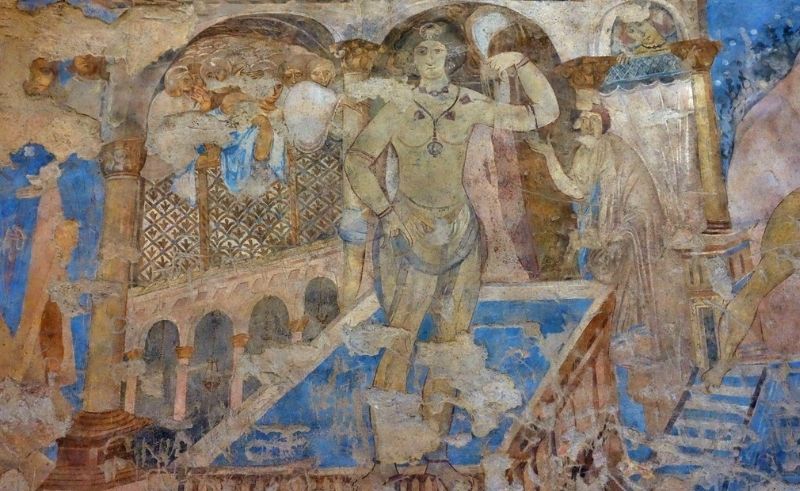

What transforms Qusayr ‘Amra from historic curiosity to architectural revelation lies on its walls. Every surface—vault, dome, lintel, arch—was once alive with frescoes. Many still are. Hunters pursue wild game with spears; acrobats twist mid-air; craftsmen hammer, weave, and forge; musicians pluck strings in painted notes. There are personifications of the seasons, women crowned in petals, kings identified by Greek inscriptions, even depictions of animals rarely seen in the region by Walid’s time.

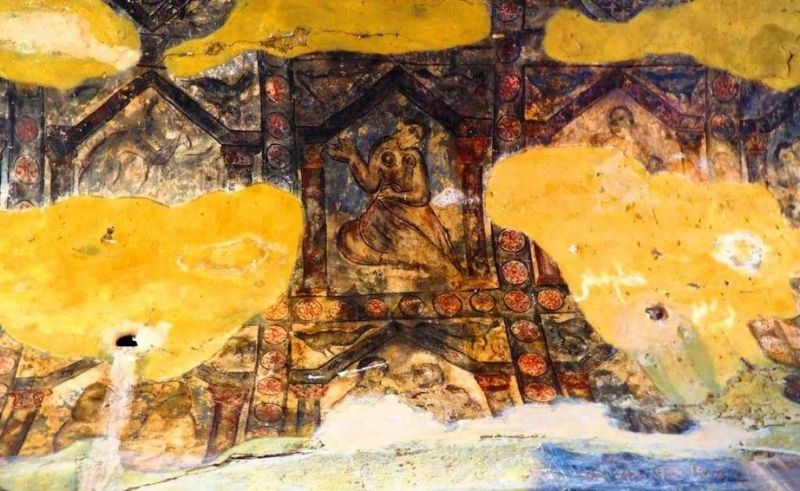

And on the dome of the hot room, preserved against centuries of desert wind, spreads one of the earliest known celestial maps in Islamic art: the zodiac arranged in orbit, constellations floating over the bathing pool like guardians of the night sky.

Qusayr ‘Amra was never meant to be an urban palace. It was a desert escape, a place where the prince and his companions could withdraw from Damascus, hunt in the surrounding steppe, and bathe under painted stars. Its water reached the complex through an ingenious system of shallow wells and channels—proof that even in the middle of nowhere, luxury was non-negotiable.

Today, Qusayr ‘Amra stands as one of Jordan’s six UNESCO World Heritage Sites, celebrated not for grandeur but for its rarity. Few early Islamic structures preserve their wall paintings. Fewer still offer such a complete narrative of how a desert retreat once looked, felt, and functioned.

- Previous Article Riyadh–Jeddah Railway to Be Delivered in Phases by 2034

- Next Article The Middle Eastern Pulse of Leighton House

Trending This Week

-

Mar 11, 2026