A Forgotten Home in Islamic Cairo is Revived Into a Cultural Haven

Across from Ibn Tulun Mosque, architect Mona Zakaria revives a forgotten house, transforming it into a cultural space where architecture and art reconnect Cairo with its memory.

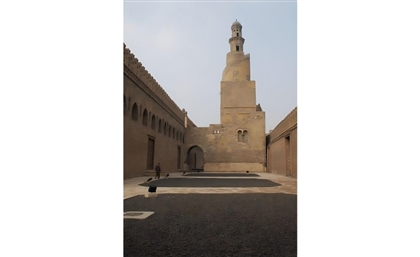

In front of the grand Ibn Tulun Mosque, hidden within the layered textures of Historic Cairo, stands a modest three-story house called ‘Matlaa’, a word that describes a typology even smaller than the traditional Islamic Raba’. For decades, it was abandoned, quietly watching centuries unfold across the mosque courtyard. In 1998, architect Mona Zakaria walked by, felt its pull, and decided to bring it back to life.

“I was walking by and I found this abandoned place, no windows, no doors, full of trash,” Zakaria tells SceneHome. “But I felt the energy of the place, despite all the ugliness and neglect. It’s like falling in love.” Locals told her it had been waiting for her since 1954.

For years, Beit Tulun remained her architecture studio, a refuge amidst the chaos of Cairo. “Because of the financial constraints, I stopped before it was done,” she recalls. “But my daughter Mariam encouraged me to continue. Now I feel like it deserves to become a cultural hub for people to interact with and build a bond with.”

-90de0a9d-f02c-4ec9-8eda-bc59b540b678.jpg) Zakaria has spent decades documenting and restoring Cairo’s architectural memory, from Souq el Fustat to Palace Omar Tousson in Zamalek. “When you renovate, you rediscover,” she says. “You weave history and architecture together. None can be alone.”

Zakaria has spent decades documenting and restoring Cairo’s architectural memory, from Souq el Fustat to Palace Omar Tousson in Zamalek. “When you renovate, you rediscover,” she says. “You weave history and architecture together. None can be alone.”

-07c01706-5fee-4f34-b0a9-5f5fe557a9c2.jpg) The house itself embodies that weaving. Its compact structure opens upward, each level unfolding toward a view, from the intimate inner balcony to a roof terrace that faces the graceful spiral minaret of Ibn Tulun. The textures of its plaster, the soft geometry of its arches, and the way sunlight filters through its openings all make Beit Tulun feel like a memory from the era of Abbasid architecture.

The house itself embodies that weaving. Its compact structure opens upward, each level unfolding toward a view, from the intimate inner balcony to a roof terrace that faces the graceful spiral minaret of Ibn Tulun. The textures of its plaster, the soft geometry of its arches, and the way sunlight filters through its openings all make Beit Tulun feel like a memory from the era of Abbasid architecture.-36eeb62a-1b18-4b0e-9279-598c1a3e71f3.jpg) In 2025, Downtown contemporary arts festival - DCAF debuted Beit Tulun’s new life as a public cultural space, marking the beginning of a new chapter. The first artist to exhibit there is Basma Osama, an Egyptian ceramicist who has lived in Canada for 30 years. “I don’t know if I chose Beit Tulun or if we both chose each other,” she says. “The fit was so obvious. As soon as I entered, I felt at home, and when I set up the exhibition, the pieces felt like they belonged to the house.”

In 2025, Downtown contemporary arts festival - DCAF debuted Beit Tulun’s new life as a public cultural space, marking the beginning of a new chapter. The first artist to exhibit there is Basma Osama, an Egyptian ceramicist who has lived in Canada for 30 years. “I don’t know if I chose Beit Tulun or if we both chose each other,” she says. “The fit was so obvious. As soon as I entered, I felt at home, and when I set up the exhibition, the pieces felt like they belonged to the house.”

-fadcd723-90c7-4736-a666-8839f4b8489b.jpg) Osama’s ceramics carry traces of Egypt. It is tactile, imperfect, and instinctive. “People told me they could see Egypt in my work,” she says. “It’s like memories resurface spontaneously through the clay, bearing witness to my Egyptian identity.”

Her exhibition, ‘Reminiscence: From Memory and Matter’, pays homage to pottery as an ancient container of meaning. “For me, the vessel is everything, it holds, it preserves, it remembers,” Osama explains. One piece recalls the sand and rock of Ain Sokhna, where she played as a child. Another draws from ‘tameema’, a traditional Egyptian amulet meant to protect its owner from envy rendered in clay and wood.

Returning to Cairo to show her work was, for Osama, an artistic milestone. “It’s been 30 years since I left,” she says. “Coming back and realising that your roots are still there, that belonging still lives inside you, it’s harmony. It’s something that had to happen.”

The pairing of Zakaria and Osama feels almost fated: one reviving architecture, the other reviving memory. Beit Tulun became a vessel itself, to hold life, art, and purpose.

Osama’s ceramics carry traces of Egypt. It is tactile, imperfect, and instinctive. “People told me they could see Egypt in my work,” she says. “It’s like memories resurface spontaneously through the clay, bearing witness to my Egyptian identity.”

Her exhibition, ‘Reminiscence: From Memory and Matter’, pays homage to pottery as an ancient container of meaning. “For me, the vessel is everything, it holds, it preserves, it remembers,” Osama explains. One piece recalls the sand and rock of Ain Sokhna, where she played as a child. Another draws from ‘tameema’, a traditional Egyptian amulet meant to protect its owner from envy rendered in clay and wood.

Returning to Cairo to show her work was, for Osama, an artistic milestone. “It’s been 30 years since I left,” she says. “Coming back and realising that your roots are still there, that belonging still lives inside you, it’s harmony. It’s something that had to happen.”

The pairing of Zakaria and Osama feels almost fated: one reviving architecture, the other reviving memory. Beit Tulun became a vessel itself, to hold life, art, and purpose.

- Previous Article Egypt Qualifies for 2026 FIFA World Cup After 3-0 Djibouti Win

- Next Article Inside Egypt’s Seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Trending This Week

-

Jan 31, 2026