This Couple Uncover Alexandria’s 'Footnotes' on Walking Tours

Fueled by their own love story, Juan and Wafaa’s tours are a cross-cultural project to actively read Alexandria—uncovering the hidden biographies and forgotten dramas embedded in its very sidewalks.

The trouble with love at first sight, of course, is the problem of sight itself. It’s a notoriously unreliable witness. It can be swayed by a trick of the light, the cut of a jacket, the specific arch of an eyebrow over a mask. It tells us nothing of how someone takes their coffee, or what they are like when they are tired, or whether they will remember the day, years later, as the 15th of February or the 23rd of May. Biology offers its shrug: a cascade of oxytocin, a bit of evolutionary programming for pair-bonding, a selfish gene cheering from the sidelines.

History, meanwhile, presents its case studies with a raised eyebrow: Cleopatra’s calculated sail into Mark Antony’s view, Dante’s lifelong muse Beatrice glimpsed at nine, Shah Jahan’s glance in a bazaar that ultimately froze grief in marble. These legendary first glances built monuments and toppled empires; they were as often preludes to ruin as to creation. Sociology scoffs at the naïvety of the whole ordeal. And yet, entire lives, cities, destinies are still rerouted on the strength of that glance. The real question isn’t whether it exists, but what you manage to build on that dizzying, flimsy foundation once the chemicals settle.

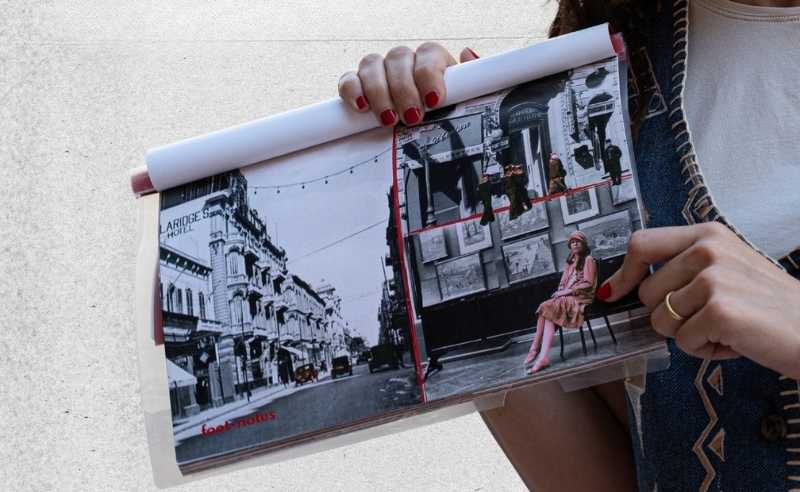

Egyptian-Guatemalan couple Wafaa and Juan, with their mismatched calendars and complementary gazes, are offering an argument for that fleeting glimpse. What they built from that glance, from the merging of her deep-local knowledge and his outsider’s curiosity, is Footnotes, a series of walking tours through Alexandria. They take you down streets you’ve passed a hundred times (or are yet to experience for the first) and show you the ghost-lives clinging to the architecture, the love affairs and bankruptcies and artistic triumphs embedded in the limestone.

Wafaa was giving a tour of the Antiquities Museum in the Bibliotheca Alexandrina when she first saw him. He was just another visitor, a friend of a friend from Guatemala, which to her then was an abstraction, a smear on a map. He was wearing a mask. All she had were his eyes. He, for his part, had her voice —passionate, explaining the history of her country— and a certain energy he describes as “immediately magnetic.” He plotted, clumsily, for her number, inventing a fragility about being a lonely expat with no friends, no Arabic, no way to navigate the city. She handed over her digits, showed him around. For her, it was a friendly gesture for a stranger. For him, every coffee, every walk along the Corniche, was a date. “It’s just that, for me, we were already on a date. She thought we should go. I thought we were going.”

This mismatch in perception would become a pattern, a charming, gentle friction. Wafaa, the Alexandrian Egyptologist, thinks. She analyses, she turns things over in her mind for months. Juan, the Guatemalan former UN cultural mediator, acts. He quit his job on a whisper of a dream to study Arabic in Alexandria because a novel he read at twelve, The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho, planted the idea and he’d saved up the money to make it real. When he decided he was interested, he was interested. When she decided, three months later, to officially start dating, his visa was expiring in seven days.

So their love story, born in the shadow of ancient scrolls, immediately became a thing of air miles and video calls. He was forced to leave; she stayed, and their relationship lived in the ether, a digital bridge between Egypt and Italy, where Juan found work. This distance, ironically, was their ally. Introducing a foreign suitor to a traditional Egyptian family is one thing; introducing a suitor who is continents away, visible only through a screen, is another.

But this is not just a story about how two people found each other. It is about how two people, once found, went about finding their city.

Alexandria can be a difficult city to love on purpose. Not exactly post-card-ish; it is a lived-in, weathered, glorious mess of a place where history leaks out of the cracks in the pavement, whispers from the Art Deco curves of a dilapidated apartment block, lingers in the scent of roasting chickpeas and salt air. Wafaa and Juan, like many young Alexandrians, had fallen into a rut. Weekends meant an automatic, wearying pilgrimage to Cairo. “We were fed up with passively perceiving our city,” Wafaa says. “It was ingrained in our brains that we cannot have fun unless we go to Cairo.” Alexandria was where you worked, slept, and waited to leave. Cairo was where things happened.

One February, they stopped. They decided to become tourists in their own home. “I really enjoy the adventure of discovering something new. So when we were just doing this routine trip to Cairo, it felt static. We decided to build our own adventure.” Juan explains. They went back to the Bibliotheca, the site of their meeting, and pulled books. They chose Fouad street, a bustling artery—and decided to learn it, every building, every story. They were, as Wafaa puts it, “scratching the surface with our nails. Alexandria is something we will never finish. It took us one year to research one kilometre of 20th-century Alexandria. Not from the beginning of time—just one thousand meters of one century."

They walked, they took notes, they fell into rabbit holes of municipal archives and forgotten biographies. What began as a personal project to cure their own boredom soon curdled into a shared conviction: they had to tell someone.

The name came through a playful collision of words. Feet on the street. Notes in a book. Footnotes. It was perfect—an academic term made literal, a promise of marginalia, of hidden stories waiting to be brought into the main text. They read the city so they can walk it (and in turn walk their participants) better.

They posted their first tour on an expat Facebook group. On the morning of the walk, crippled by nerves, they made a pact: if no one showed up, they would simply go for a coffee and pretend it never happened. One man showed up. A Turkish expat. He became, instantly, a friend. The tour had worked.

What they had tapped into was a silent, collective hunger. They expected interest from other foreigners, but were stunned when Alexandrians —young professionals, elderly ladies with portable chairs— began to sign up. People were starving for the narrative of their own city, for the connective tissue between the Alexandria of Cavafy and Forster and the Alexandria of their daily commute. Footnotes grew, organically, through whispers and Instagram stories. Then, last November, they collaborated with the French cultural institute. They expected thirty people. One hundred turned up.

Picture it: a hundred people, a moving mass, trying to navigate Alexandria’s famously anarchic sidewalks without microphones (which are illegal for such gatherings). Juan and Wafaa had to scream, to translate on the fly between English and Arabic, to become a kind of theatrical, double-act beacon at the centre of a human tide. Despite the urban cacophony, the crowd leaned in, straining to hear. An elderly lady followed the entire three-hour route, dragging her little stool from stop to stop, a one-woman testament to the power of a story well told.

What they had tapped into was a silent, collective hunger. They expected interest from other foreigners, but were stunned when Alexandrians —young professionals, elderly ladies with portable chairs— began to sign up. People were starving for the narrative of their own city, for the connective tissue between the Alexandria of Cavafy and Forster and the Alexandria of their daily commute. Footnotes grew, organically, through whispers and Instagram stories. Then, last November, they collaborated with the French cultural institute. They expected thirty people. One hundred turned up.

Picture it: a hundred people, a moving mass, trying to navigate Alexandria’s famously anarchic sidewalks without microphones (which are illegal for such gatherings). Juan and Wafaa had to scream, to translate on the fly between English and Arabic, to become a kind of theatrical, double-act beacon at the centre of a human tide. Despite the urban cacophony, the crowd leaned in, straining to hear. An elderly lady followed the entire three-hour route, dragging her little stool from stop to stop, a one-woman testament to the power of a story well told.

The tours crystallise their dynamic. Juan is the curator of the big picture, Wafaa the archivist. They filter everything through a simple question: “does this forgotten life, this fragment, tell us something valuable about how to live our own?”

The tours crystallise their dynamic. Juan is the curator of the big picture, Wafaa the archivist. They filter everything through a simple question: “does this forgotten life, this fragment, tell us something valuable about how to live our own?”

Their first tour, ‘Seeking Beauty in Alexandria’, was born from a personal need to find it. It walks the length of Fouad Street, beginning at the site of the ancient Gate of the Sun bridging millennia by reading from the second-century romance Clitophon and Leucippe, where the protagonist’s eyes are “filled with the light” of the city—a feeling they aim to resurrect. The tour winds past architectural milestones, but the stories are of the individuals woven into the fabric ending at the Greco-Roman Museum, a full stop that begs for a sequel.

‘Ink, Film, and Stone’ explores the second half of their street-level symphony. The ‘ink’ refers to writers like modern Greek poet C.P Cavafy; pointing to the apartment where the poet of desire and memory lived, framing the very window from which he watched the same street. The ‘film’ is the ghost-light of the great cinemas—the Amir, the Metro, the Royale—palaces where Egypt dreamed in flickering silver and collective gasp. And the ‘stone’ is everything else: the Opera House’s silent grandeur, the façade of the Sayeda, the very sidewalk beneath your feet. Each cornice, balcony, and arched doorway is presented as the deliberate artistic signature of an Italian, Greek, or Armenian architect who, like Juan, arrived in Alexandria and decided to leave a piece of their soul in its mortar. This tour posits that the city itself is a communal, unfinished artwork, and to walk it with them is to trace the brushstrokes.

Their latest, born of research that began last August, is ‘Flashback in a Garden’, a collaboration with a local deli for a picnic within the grounds of the Montaza Palace. They dig into the palace’s secretive past as a royal enclave, its transformation into a public park, and the Hellenistic ruins hidden within its gardens. A tour about the layers; what opens up and what gets lost when a private paradise becomes public space.

The texture of Footnotes is in the details. They’ll stop at Chez Gabi and note that the paintings on the wall are by Bernard de Zogheb, the last of a legendary Alexandrian family, a friend of the owner. They link the roz bel laban (rice pudding) at Sheikh Wafik to the arroz con leche of Juan’s Guatemalan childhood. “I always thought that dish was Guatemalan,” he says. “I was completely sure. And when I came here, I discovered, of course, everything at the end of the day is Egyptian.”

‘Ink, Film, and Stone’ explores the second half of their street-level symphony. The ‘ink’ refers to writers like modern Greek poet C.P Cavafy; pointing to the apartment where the poet of desire and memory lived, framing the very window from which he watched the same street. The ‘film’ is the ghost-light of the great cinemas—the Amir, the Metro, the Royale—palaces where Egypt dreamed in flickering silver and collective gasp. And the ‘stone’ is everything else: the Opera House’s silent grandeur, the façade of the Sayeda, the very sidewalk beneath your feet. Each cornice, balcony, and arched doorway is presented as the deliberate artistic signature of an Italian, Greek, or Armenian architect who, like Juan, arrived in Alexandria and decided to leave a piece of their soul in its mortar. This tour posits that the city itself is a communal, unfinished artwork, and to walk it with them is to trace the brushstrokes.

Their latest, born of research that began last August, is ‘Flashback in a Garden’, a collaboration with a local deli for a picnic within the grounds of the Montaza Palace. They dig into the palace’s secretive past as a royal enclave, its transformation into a public park, and the Hellenistic ruins hidden within its gardens. A tour about the layers; what opens up and what gets lost when a private paradise becomes public space.

The texture of Footnotes is in the details. They’ll stop at Chez Gabi and note that the paintings on the wall are by Bernard de Zogheb, the last of a legendary Alexandrian family, a friend of the owner. They link the roz bel laban (rice pudding) at Sheikh Wafik to the arroz con leche of Juan’s Guatemalan childhood. “I always thought that dish was Guatemalan,” he says. “I was completely sure. And when I came here, I discovered, of course, everything at the end of the day is Egyptian.”

This meticulousness extends to every part of the endeavour. Wafaa, who claims no prior expertise, taught herself graphic design, now crafting their Instagram posts—a mix of elegant typography, historical photographs, and playful, hand-drawn cartoons. Their visual identity is a warm, earthy red, inspired by the pigments of Mayan pyramids.

“We don’t want Footnotes to grow faster than us,” Juan says. They talk about organisational spreadsheets as a form of moral philosophy. Growth through quality and depth. The community they’ve built—“people wanted to join us to celebrate their birthdays on our tour”—is the real yield.

At the end of my call with them, I found myself scrolling through their Instagram, looking at the pictures of the hundred-person tour, the lady with her chair, the vibrant graphics. I thought about love at first sight. Not the biological imperative or the sociological trope, but the practical result of it. Sometimes, that first unreliable glance leads to a shared life. And sometimes, that shared life decides to turn itself outward, to become a collective act of looking—slowly, carefully, lovingly—at everything that was already there. To read the city so they, and all who walk with them, can walk it better as a series of footnotes, patiently compiled, waiting to change the story.

This meticulousness extends to every part of the endeavour. Wafaa, who claims no prior expertise, taught herself graphic design, now crafting their Instagram posts—a mix of elegant typography, historical photographs, and playful, hand-drawn cartoons. Their visual identity is a warm, earthy red, inspired by the pigments of Mayan pyramids.

“We don’t want Footnotes to grow faster than us,” Juan says. They talk about organisational spreadsheets as a form of moral philosophy. Growth through quality and depth. The community they’ve built—“people wanted to join us to celebrate their birthdays on our tour”—is the real yield.

At the end of my call with them, I found myself scrolling through their Instagram, looking at the pictures of the hundred-person tour, the lady with her chair, the vibrant graphics. I thought about love at first sight. Not the biological imperative or the sociological trope, but the practical result of it. Sometimes, that first unreliable glance leads to a shared life. And sometimes, that shared life decides to turn itself outward, to become a collective act of looking—slowly, carefully, lovingly—at everything that was already there. To read the city so they, and all who walk with them, can walk it better as a series of footnotes, patiently compiled, waiting to change the story.

- Previous Article Egyptian-Canadian Brand Kotn Opens Hotel for Creatives in London

- Next Article SELECTS: Stylist Faheem Ismail Takes on the Modern Abaya

Trending This Week

-

Feb 07, 2026