The Art of Exploring Foreign Identities at the Venice Biennale

Art curator and CairoScene contributor Sophie Kazan attended the Venice Biennale’s preview week, giving us a glimpse into some of the most exciting and innovative pavilions and ancillary events.

With its 60th edition underway, the Venice Biennale has reached beyond the boundaries of nations and artforms with the assignment of their first Latin American curator. Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa chose the theme of ‘Foreigners Everywhere, Stranieri Ovunque’, in order to bring exposure to artists from the Global South. Art curator and CairoScene contributor Sophie Kazan attended the Venice Biennale’s preview week, giving us a glimpse into some of the most exciting and innovative pavilions and ancillary events that are being held by rising and established artists from across the Arab world.

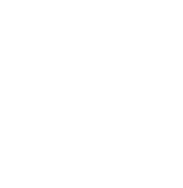

'Black is Beautiful' (1969), Samia Halaby, Palestine

'Black is Beautiful' (1969), Samia Halaby, Palestine

“… Wherever you go and wherever you are you will always encounter foreigners— they/we are everywhere,” said Pedrosa, as part of his announcement of the theme of this year’s global art event. He said that this biennale would favour artists who had never been included in a biennale before and added, “… No matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.” With 88 national pavilions included in the event, it was exciting to see many nations involved in the Venice Biennale for the first time, including two newly-included Latin American countries, one East Asian country and several African countries, either with their own pavilion or within the main Biennale Arte exhibition. These countries include the United Republic of Tanzania, Ethiopia, Senegal, the Republic of Benin, Nicaragua, the Republic of Panama and the Democratic Republic of Timor Leste.

'Untitled' (1965), Etel Adnan, Lebanon

'Untitled' (1965), Etel Adnan, Lebanon

Special Biennale Jury mentions went to the Argentinian artist, La Chola Poblete, and veteran Palestinian abstract artist, Samia Halaby. Halaby’s painting, ‘Black is Beautiful’ (1969), is part of the biennale’s central ‘Nucleo Storico’ exhibition, curated by Pedrosa. The Biennale Arte included a global array of artists. From Lebanon, Etel Adnan’s charming ‘Untitled’ (1965) is an oil painting on a modeset and unevenly shaped canvas. It explores landscape in terms of shapes and contrasting colours. On a larger scale, the Moroccan Mohamad Chabâa’s abstract ‘Composition’ (1974) is a broad, white canvas which includes the artist’s characteristic brand of colourful and architectural linear designs. An installation that is hard to miss in the Arsenale galleries is Dana Awartani’s colourful panels of yellow and orange silk that stretch across the width of the space. Entitled ‘Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones’ (2024), this installation is a memorial of sorts to the destruction of so many important historical sites throughout the Arab world that have been destroyed through war. The Palestinian-Saudi artist has carefully darned the holes and rips in the silk as a caring act of healing and renewal.

'Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me heal your broken bones.' (2024), Dana Awarti, Palestine/ Saudi Arabia

'Come, let me heal your wounds. Let me heal your broken bones.' (2024), Dana Awarti, Palestine/ Saudi Arabia

Meagan Kelly Horsman, Managing Director for Christie's Middle East, felt that Pedrosa’s theme of inclusivity and visibility for artists was “by far the most exciting that I have attended.” She added, “To see a plethora of Middle Eastern artists across the Arsenale and Giardini’s main pavilions, coupled with robust national pavilion representations, was to see a new framing of the global art historical canon on an international stage.” In terms of national representation, she tells me that the biennale’s five Arab pavilions - Egypt, Lebanon, Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia - had inspired her. “I felt a sense of a commandeering of history and turning it on its head – from Wael Shawky’s operatic film [in the Egyptian pavilion] to Munira Al Solh’s multimedia presentation exploring Phoenician history and mythology [in the Lebanese pavilion].”

A great many visitors to the Arsenale portion of the biennale, and myself included, found the solo exhibition of Emarati artist Abdullah Al Saadi, curated by Tarek Abou El Fetouh, a soothing respite from the buzz and excitement of this extensive international display. ‘Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia’ is a testament to the artist’s lone journeys in the wilderness, sometimes on foot and sometimes by bicycle, near Khorfakkan, his home on the Eastern coast of the UAE bordering the Gulf of Oman. The exhibition includes found objects, including rocks onto which the artist has made marks and transcribed with contour lines, similar to those found on a map to show elevations in the landscape. These are echoed in the white lines of light running just below the ceiling of the exhibition space. Drawings and paintings on pieces of paper, on scrolls and fitted into chocolate or biscuit tins are displayed and also stored in the large, colourful travelling trunks that line the far wall of the exhibition space. The exhibition is intended to emulate the artist’s studio in its air of informality and in the dispersal of art around the room.

-bcba8bb3-2c78-4f53-bdba-2857548cde7f.jpg)

'Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia', Abdullah Al Saadi, UAE

El Fetouh has worked with Al Saadi before at Expo 2020. His choice to include a performance in the exhibition - done by young actors from the Sharjah Performing Arts Academy who are in Venice on rotation from the UAE - as a way of bringing the various objects together is ingenious and effective. The performers have been guided by the artist himself and briefed by the curator, and will be present throughout the pavilion’s time in Venice over seven months. They will open the boxes and their contents to visitors, allowing them to embark on their own course of discovery through AlSaadi’s work. This personal and human touch is important to both the curator and the artist, whose desire to get away from technology and impersonal communication are one of the reasons that he would embark upon these artistic journeys.

'Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia', Abdullah Al Saadi, UAE

'Sites of Memory, Sites of Amnesia', Abdullah Al Saadi, UAE

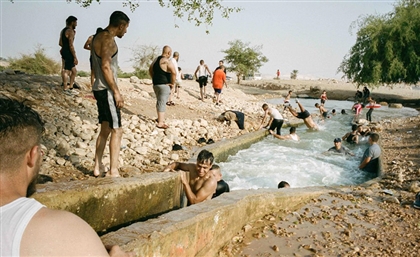

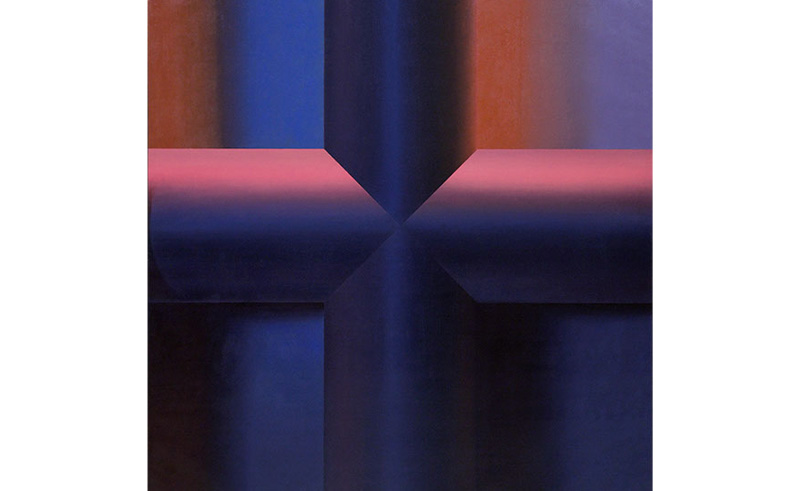

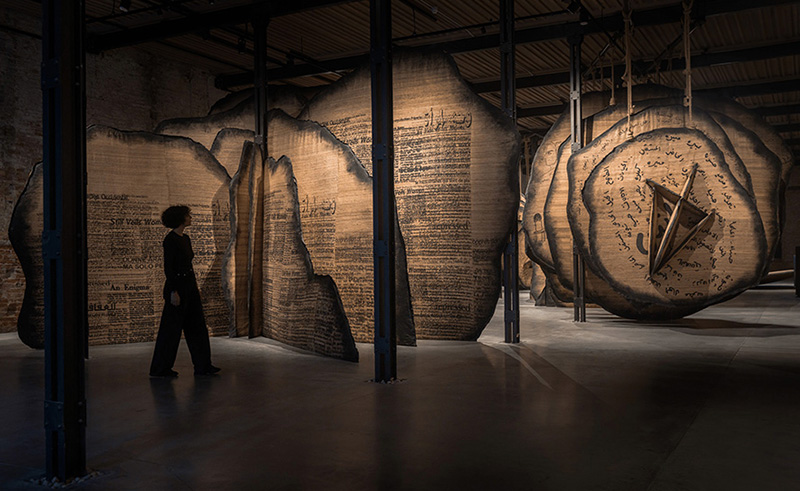

Nearby, Manal Al Dowayan’s solo-exhibition for the Saudi Arabian pavilion, ‘Shifting Sands: A Battle Song’, is a multimedia and multi-layered installation. It concentrates upon the framing of women’s roles within Saudi society, the country’s media and ‘collective memory’. Soft sculptures resembling giant, rolling desert dunes, are printed with words, pictures and imagery evoked by the artist’s conversations with Saudi women. There are also sound recordings of women and girls singing in Arabic, and the effect is extremely moving. Al Dowayan tells me how touched she had been by the enthusiasm and trust of women from throughout Saudi Arabia whom she worked with leading up to her work at Venice. Though genders couldn’t mix in the past, we speak about the exciting changes in Saudi culture over the past decade, particularly in the role of women in society, which forms a large part of Al Dowayan’s work. She tells me that her recent workshops for art projects in the desert town of Al Ula, were for the whole community. “This was a transformative approach for me and I love it,” Al Dowayan shares. “This might be the last time that I just work with women… We [women and men] are beginning to occupy one public sphere and one thinking space… men are interested in collaborating with women and thinking about the future and I’m happy to open that up and think about it as part of my conversation.” When I ask her if she had feedback from men about her work, she jokes, “There were a lot of complaints from men that they were not invited for these sessions!”

'Shifting Sands: A Battle Song', Manal Al Dowayan, Saudi Arabia

If this is the principal portion of the Venice Biennale, it is by no means the most important part! There are many exciting ancillary exhibitions and presentations by artists, galleries and museums who wish to take advantage of this rare moment when the global art scene descends on a lagoon of approximately one hundred Adriatic islands, which host one of the largest art events of the art calendar. Three exhibitions that particularly stood out this year were from Qatar, Abu Dhabi and Morocco.

‘Your Ghosts Are Mine, Expanded Cinemas’ is Qatar Museums’ presentation of films from the Arab World and Global South in the Palazzo Franchetti that will soon form an exciting curation of films in the future Art Mill Museum in Doha. The exhibition is an immersive journey through ten galleries, each of which each draw together a wide selection of films from the Arab world and Global South, related to themes such as ruins, desert voices, exile and deserts. Documentaries, feature films, short films, animations and memoires from the Doha Film Institute (DFI) archive, amongst others, present a new form of curation. It is fascinating to walk around a space that has been so thoughtfully arranged by curator and film-maker, Matthieu Orléan. “Cinema is not only the mirror of political changes: it participates in them, anticipates them, accompanies them, supports them, transforms them in a daring aesthetical approach,” Orléan says.

-0941d0a6-1fa8-484f-a38d-4a03a4ffa49b.jpg) ‘Your Ghosts Are Mine, Expanded Cinemas’

‘Your Ghosts Are Mine, Expanded Cinemas’

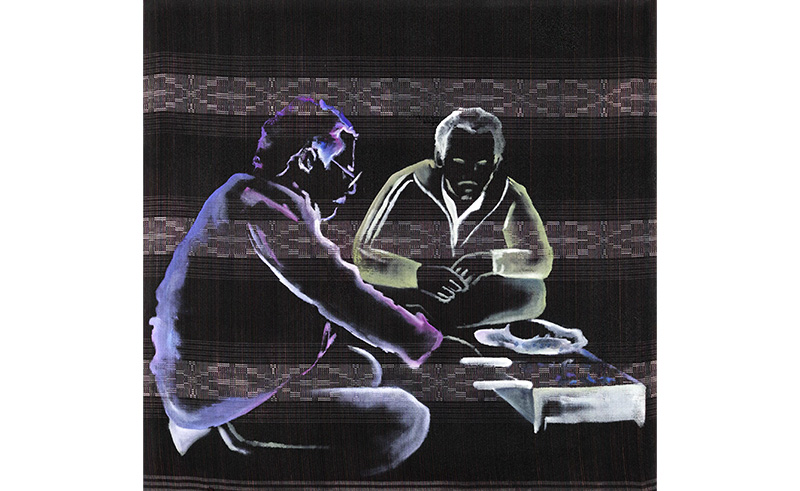

Another important highlight of the biennale’s collateral events is Abu Dhabi Art’s annual ‘Beyond Emerging Artists’ (BEA) project. Shown at the Marignana Arte Gallery, this year the BEA is presented by the celebrated curator Morad Montazami, Director of Zamân Books & Curating. His Casablanca Art School exhibition has been shown at the Tate Gallery St Ives in England and is now at Sharjah Art Foundation in the UAE, before it travels to Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt next year. The BEA exhibition shows work by three artists, whose work varies greatly in terms of concept and materiality. Almaha Jaralla’s ‘Crude Memory’ features works in oil on textile that reflect the history of Al Ruwais near Abu Dhabi. Al Ruwais is a city in the South of the UAE, which has been transformed by the country’s crude oil industry. Jaralla reflects on the transformation of cities over time and through the growth of industry.

'Crude Memory', Almaha Jaralla, UAE

'Crude Memory', Almaha Jaralla, UAE

Samo Shalaby is a Palestinian-Egyptian installation artist who explores various international art historical narratives and techniques, including theatrical devices to explore shifting perspectives, real and surreal environments. “It’s about passion and the space in which theatricality, art history, contemporary art, contradiction, the surreal and science fiction collide, as well as the various dichotomies like dark and light, real and unreal, private and public. In my ‘What Lies Beneath’ series I am particularly looking at the fold, what’s behind the fold and in front of it – intimacy and audience.”

-015e6f35-c446-40c9-af5b-486d18965da2.jpg) 'What Lies Beneath', Samo Shalaby, Egypt/ Palestine

'What Lies Beneath', Samo Shalaby, Egypt/ Palestine

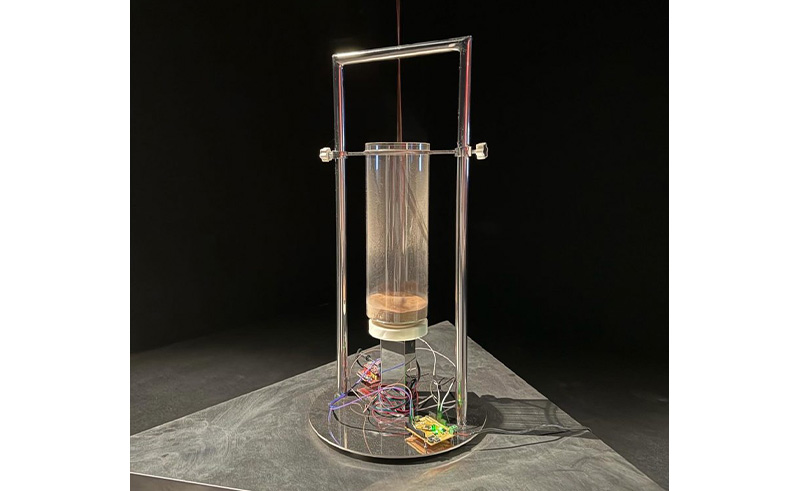

Latifa Saeed’s four ‘Dust Devils’ installations see the artist working with projections, technology and sound to conjure up atmospheric phenomena based on the four classical elements - Air, Fire, Water and Earth - to tremendous effect. One is an electro-magnetic device reacting with sand to emulate the effects of a tornado, while another is a soundscape of vibrations composed by Saeed. Through her art, Saeed appears to be commenting on the fragility of humanity and the environment. “The experimental artworks evoke a sense of wonder and contemplation,” she says. “I create a dialogue between nature and innovation.”

'Dust Devils', Latifa Saeed, UAE

'Dust Devils', Latifa Saeed, UAE

‘When Solidarity Is Not A Metaphor’ was the powerful title of Dubai’s ‘Arsekal Initiatives’ exhibition, curated by Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, the head of the artistic programme of the Paris-based artists’ residency, the Cité des Arts (CDA). “The project came together as we began to think about the current moment and the people who are suffering so much at this moment in various places,” Petrešin-Bachelez says. The artists in the CDA are often exiled from their countries. When the space was first founded, almost 60 years ago, this meant they were from countries that were part of the former Soviet Union, as well as countries like Palestine and Ukraine.

The exhibition is based on a paper titled ‘Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor’ which was written by Tuck and Wayne Yang to analyse illegal settlements, the politics of belonging and the guilt of survivors. Invited artists include artists and Cité des Arts alumni, Dima Srouji and Jasbor Puar, who present the fascinating installation, ‘Revolutionary Enclosures (Until the Apricots)’ (2023). This is a little room in the exhibition, lined with comfortable chairs and which is covered with what appears to be pretty pink, flowery wallpaper. In fact, the room depicts Srouji’s grandmother’s wallpaper in her living room in Bethlehem and the flowers around the wall symbolise the dark bullets, shown here in the centre of the petals, embedded as if into human flesh. On the wall is a black and white photograph by Srouji of the coffee pots, glasses and what looks like a row of bullets on part of the ancient Church of the Nativity, when it was under siege by Israeli forces in 2002. This, and other work by artists such as Saad Eltinay, explore the similar and yet different situations of longing, suffering and crisis undergone by people across the globe as they find creative ways to evoke their stories.

This is a modern parable of sorts and also one which perfectly evokes good intentions and also moments of unlikely discomfort. Like when you see someone looking at themselves in the mirror and wonder how to react in this personal and yet revelatory moment. The ‘foreigners’ were clearly those that were new to Venice or those that had not been granted EU visas. Marta Foresti from the LAGO Collective, tells me that Schengen European visas are granted to countries based largely upon their wealth and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). “There is a specific urgency to address the inequality, particularly in Africa, where artists, musicians and designers cannot make it to international concerts and catwalks.”

For those artists, such as Majida Khattari, that could attend the biennale, further challenges and socio-political issues arose from her own country’s government. The Moroccan artists and curator’s hopes for global recognition at the 60th Venice Biennale this year were dashed when the pavilion was suddenly cancelled. Khattari tells me that she was disappointed but not surprised. Resignation to this bureaucratic unfairness or political challenges has been echoed over the years by artists from countries from the Global South that I have spoken to, either in person or via email, who did not attend the biennale or encountered challenges along the way.

It highlights not only the importance of the art biennale for artists living outside Europe and North America, but also the determination and strength that many artists need to get their work to Venice. Despite the Moroccan decision to halt the pavilion, Khattari had created work specially for this year’s biennale’s theme and so decided to ‘go at it alone’. With the support of master glassmakers on Murano and the Berengo Foundation, the artist was able to hold a solo exhibition entitled ‘The Parade’ in Murano, the Venetian island adjacent to the fair. Her paintings and installations of wooden mannequins portraying allegorical and fictional characters using simple materials such as baskets, tubing and rubber tires to perfectly evoke the haphazard sense of foreignness and otherness evoked by the biennial’s theme. In a show of defiance and with an air of having nothing to lose, she says, “This is a subject that I have been working on for a while and that is why I absolutely wanted this biennial.”

The Venice Biennale is certainly a step in the right direction as it focuses on accessibility and inclusion. The theme chosen by Pedrosainspired many to think about their country’s socio-cultural make-up and the challenges faced by artists living under oppression. However many visitors have questioned whether it is not the Biennale itself, first founded in 1893, its layout and organisation - which has gone largely unchanged since the mid 20th century - that needs to be updated or re-appointed.

- Previous Article French Montana is Headlining Dubai’s First Eco-Festival in June

- Next Article Oman Botanic Garden to Begin Trial Run in 2024