Artist Mounira Al Solh Explores Feminine Endurance at Venice Biennale

CairoScene contributor and curator Sophie Kazan reviews this insightful reframing of ancient myths at the Lebanese Pavilion.

“[To]…endure and survive whatever the challenges.”

Showing at the Venice Biennale for the second consecutive time, the Lebanese Pavilion and its curator Nada Ghandour presented over 40 artworks by artist Mounira Al Solh. The exhibition, ‘A Dance With Her Myth’, focuses on the legend of the Phoenician Princess Europa. Art curator and CairoScene contributor Sophie Kazan visited the pavilion, where she had the opportunity to speak with the artist about the intersection between mythical narratives and the events that shaped Lebanon.

“It all started after various events in Lebanon,” Al Solh tells me. “First, we had the economic crisis and the revolution in October 2019, then the 4th August port explosion and COVID-19 in 2020. Even though I live between the Netherlands and Lebanon, I was there on both occasions and like many others at the time, these events really marked me.”

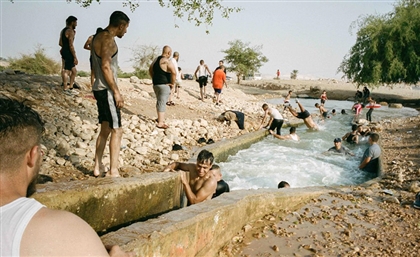

Al Solh was not alone in feeling emotionally and psychologically numb. She says that she found herself in a very dark place, filled with sorrow and pain. “There was a need to reconstruct yourself, to get out of this dungeon and be creative to kind of save your soul. I spent time with my family and visited the coast at Soor.” Soor is the Arabic name for Tyre in South Lebanon, one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world. “Around the same time, I also visited the northern coast of Lebanon and visited the Phoenician wall near the town of Batroun. It was so inspiring, and I felt that I should look back at my country’s ancient history.”

Al Solh was not alone in feeling emotionally and psychologically numb. She says that she found herself in a very dark place, filled with sorrow and pain. “There was a need to reconstruct yourself, to get out of this dungeon and be creative to kind of save your soul. I spent time with my family and visited the coast at Soor.” Soor is the Arabic name for Tyre in South Lebanon, one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world. “Around the same time, I also visited the northern coast of Lebanon and visited the Phoenician wall near the town of Batroun. It was so inspiring, and I felt that I should look back at my country’s ancient history.”

The artist recognised that the earth and its rich archaeological heritage has been a constant despite Lebanon's political turmoil. “It’s always been there for us in Lebanon and I found it so healing,” Al Solh shares. “My daughter and I would go there. It’s an escape from modern life, really!” Finding calm in the ancient past, Al Solh began to research the country’s archaeological history and Phoenician myths associated with these towns.

Al Solh found herself drawn to the creative potential of Phoenician mythology and particularly to the story of Europa. “I was researching it and then stumbled upon the story of Europa, which has been a little forgotten in Lebanon. I mean, everyone is familiar with the legend of Elissar, the daughter of the Phoenician King Belus of Tyre, and proud of the myth of Adonis, the mortal lover of the goddesses Aphrodite and Persephone from Greek mythology, but the Phoenician goddess or princess Europa is less visible. You don’t find restaurants called Europa!”

Al Solh found herself drawn to the creative potential of Phoenician mythology and particularly to the story of Europa. “I was researching it and then stumbled upon the story of Europa, which has been a little forgotten in Lebanon. I mean, everyone is familiar with the legend of Elissar, the daughter of the Phoenician King Belus of Tyre, and proud of the myth of Adonis, the mortal lover of the goddesses Aphrodite and Persephone from Greek mythology, but the Phoenician goddess or princess Europa is less visible. You don’t find restaurants called Europa!”

This developed into a healing journey for the artist and an exciting project to understand the present and the past’s place in it, reclaiming a myth that had drifted into the mists of time. She also began to focus on the goddess’ femininity within the Phoenician and Greco Roman myth. Al Solh’s original visit to Soor, it turns out, had been Europa’s birthplace and where Zeus abducted her. “So when I was approached to send a proposal for Venice, I said that I wanted to do something about the Phoenicians.”

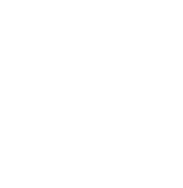

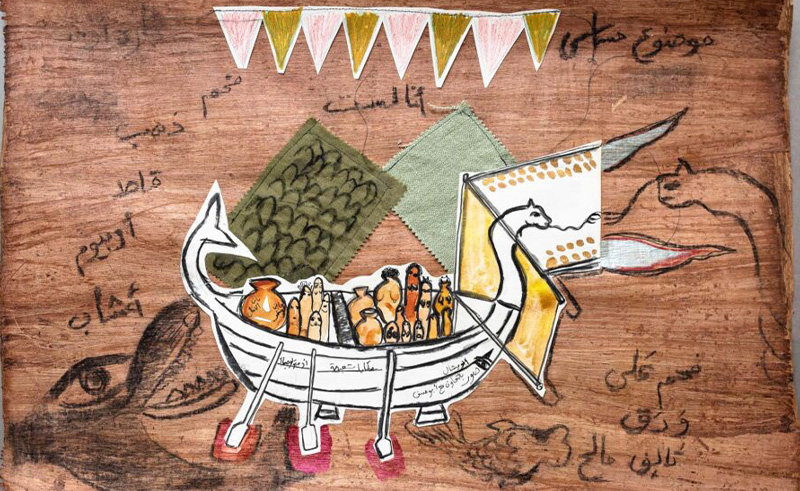

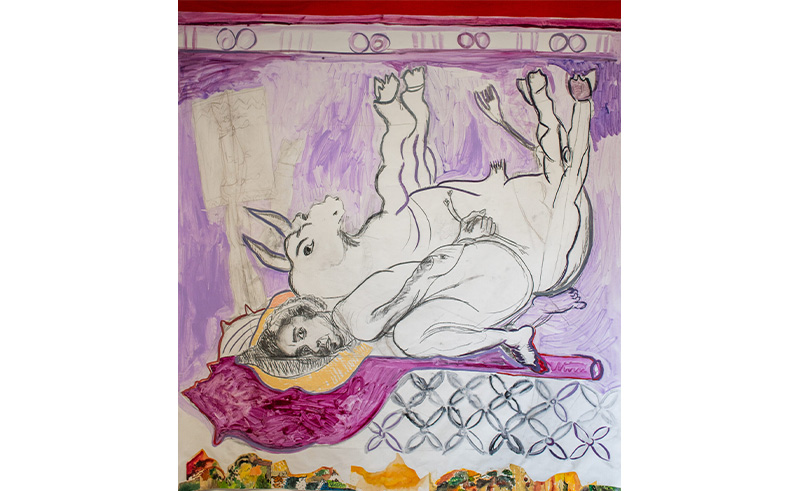

On one side of the Lebanese pavilion are hung massive, colourful canvases depicting moments in the myth of Europa – these are recognisable female forms and the unmistakable shape of the bull, into which the god Zeus transformed himself to charm the Phoenician princess before carrying her away. There is a video screen, for which Al Solh created various animation that reframe and recentre the story of Europa, as well as the frame of a boat.

On one side of the Lebanese pavilion are hung massive, colourful canvases depicting moments in the myth of Europa – these are recognisable female forms and the unmistakable shape of the bull, into which the god Zeus transformed himself to charm the Phoenician princess before carrying her away. There is a video screen, for which Al Solh created various animation that reframe and recentre the story of Europa, as well as the frame of a boat.

Al Solh worked with a family of specialist boat builders who work according to ancient Phoenician boat-building principles. “Though of course,” she insists, “we did not use cedar wood, for ecological reasons!” In reference to environmental concerns, colourful modern plastic water bottles are hung around the boat as floats.

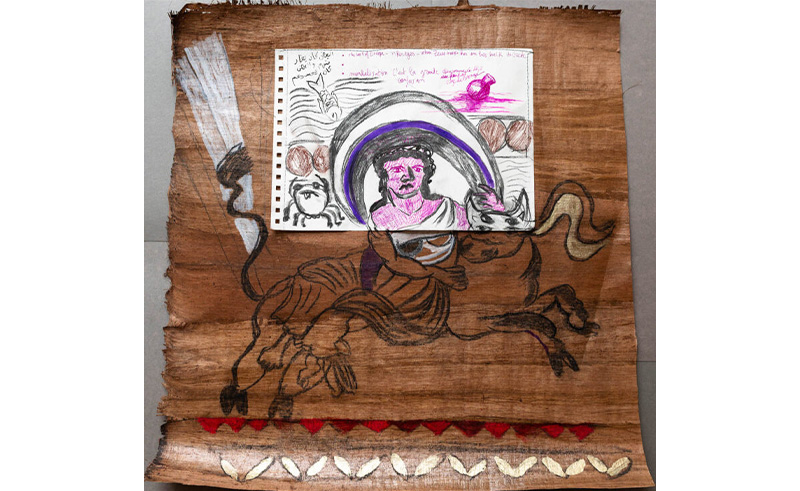

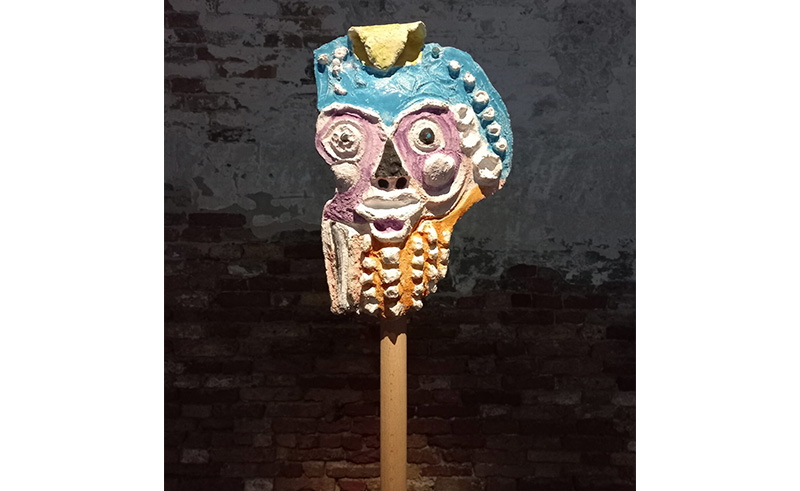

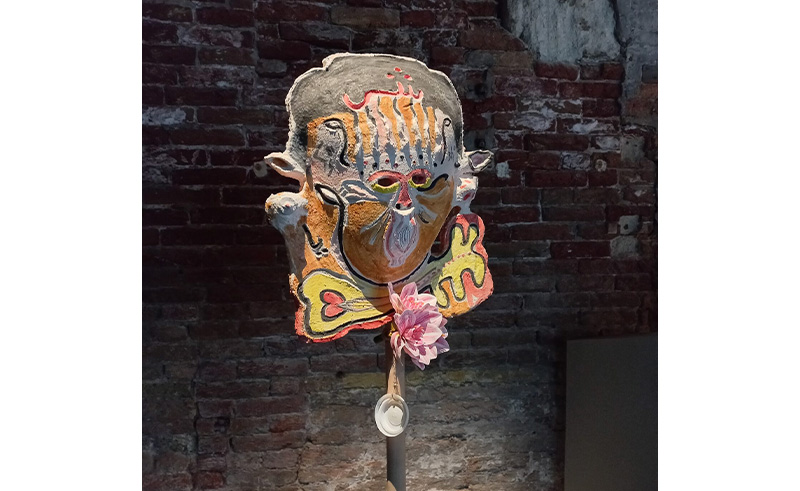

Smaller paintings, drawings, embroideries and a video also skirt the pavilion, presenting a multitude of scenes from the myth. They also show the formidable range of Al Solh’s artistic practice. “I did sculptures at art school with clay but I never really used it as a medium,” Al Solh says, “until now.” The expressive and colourful ceramic glazed masks, mounted on poles along the far wall of the pavilion, resemble Greek theatrical masks which evoke ancient ideas, or a society that is stuck in the past, according to the pavilion’s curator and commissioner, Nada Ghandour.

Smaller paintings, drawings, embroideries and a video also skirt the pavilion, presenting a multitude of scenes from the myth. They also show the formidable range of Al Solh’s artistic practice. “I did sculptures at art school with clay but I never really used it as a medium,” Al Solh says, “until now.” The expressive and colourful ceramic glazed masks, mounted on poles along the far wall of the pavilion, resemble Greek theatrical masks which evoke ancient ideas, or a society that is stuck in the past, according to the pavilion’s curator and commissioner, Nada Ghandour.

A historical scholar and heritage curator, Ghandour understood Al Solh’s desire to focus on the country’s ancient past right away, according to Al Solh. “She defended it with other members of the Lebanese pavilion’s jury who gave me feedback on ways I could develop the story effectively,” Al Solh recalls. “It was amazing!”

“Archaeology is a very important and universal language which is very interesting in terms of mythology because it can be reinterpreted in modern times,” Ghandour, who worked with co-curator Dina Bizri and architectural scenographer Karim Bekdache, tells us. “Archaeology and mythology are also important now because they allow us to criticise the present moment and subvert ideas at various levels.”

I had the opportunity to ask Dyala Nusseibeh, the Director of Abu Dhabi Art since 2016 and a renowned figure in the contemporary art world, in the Middle East, what she particularly enjoyed about the Lebanese pavilion. “The artist invites us to reconceive our ideas through a feminist lens,” Nusseibeh answers. “The artist posits that it is Europa who tricks Zeus and not the inverse, it is Europa who teaches us to endure and survive whatever the challenges, historical or contemporary, we face. As an anthem for women’s strength, resilience, humour and cunning, it’s wonderful.”

The layout of the brightly coloured pavilion, resplendent under its warm lighting and female imagery, is welcoming and warm. “The whole pavilion is an installation,” the curator tells me. “It’s not just a collection of individual works. They need to be taken together.”

The layout of the brightly coloured pavilion, resplendent under its warm lighting and female imagery, is welcoming and warm. “The whole pavilion is an installation,” the curator tells me. “It’s not just a collection of individual works. They need to be taken together.”

The resonance of the pavilion’s message is extremely dramatic but also inspiring. “We are in Venice, so everyone needs to access it and feel that it relates to their story,” Ghandour says. “But this is a Lebanese story with international resonance.” She shows me that there is a clear line of focus from both sides to the central ribbing of the boat. “The viewer is on a journey of emancipation for equality for women too, and that is why the boat is still unfinished.”